On April 30, 1975, as the Fall of Saigon plunged Vietnam into chaos, thirteen-year-old Brian Thuan Luu faced an unimaginable choice—stay and risk an uncertain future or leave behind everything he had ever known. With nothing but courage, hope, and a small flashlight given to him by his brother before his departure, Brian chose to escape on a wooden boat owned by his uncle.

“It was supposed to be a five-day journey,” Brian tells me. “But it took fifteen.”

Brian braved the treacherous South China Sea as a child with no adults taking care of him, clinging to survival as the overfilled boat became stranded on a coral reef just two days into the perilous expedition.

“After ten days stuck, the tide came in, and we floated off the reef. Two days later, a Filipino fishing boat gave us food and water and showed us how to get to a village,” he remembered. “We stayed there for seven days, sleeping on dirt roads before a navy ship took us to a refugee camp.”

Brian’s story illuminates another side of the aftermath of the two-decade war—a child’s memory of life after a war that claimed more than 59,000 American lives and some 250,000 Vietnamese.

Memory Lane

Before the communists took over, life in South Vietnam was full of opportunity and prosperity for many families.

“I was born Vietnamese Chinese,” Brian Thuan Luu recalls. “My parents owned a very successful electronics business and had an orange grove. Life was beautiful—my parents would take us on vacation every summer for one to two months.”

Born in the quiet countryside of Vĩnh Long, Brian moved with his family to Saigon at age two, where his parents expanded their business, much like a Vietnamese version of Best Buy. Their store sold televisions and electronic goods to a rapidly modernizing society. The family lived comfortably, enjoying the bustling energy of Saigon, where American soldiers were a familiar presence.

“When I was little, maybe five or six, I saw American soldiers—both white and African American. My parents encouraged me to greet them, and they would give me Wrigley’s Doublemint gum or candy. I wished I could speak English back then.”

But everything changed when the North Vietnamese communists seized control of South Vietnam on April 30, 1975. The fall of Saigon marked the end of life as Brian knew it. His family’s business was no longer theirs—private ownership was abolished, and the new regime confiscated everything. The once-thriving city was now under strict communist rule, where fear and rationing replaced prosperity and freedom.

“Our lives turned upside down. After the war, things got worse. A few years later, they (the government) changed the currency again, which meant my parents had no real income,” he says.

The Vietnamese people were forced into ideological reeducation, and those associated with the former South Vietnamese government or capitalist ventures were targeted. The vibrant Saigon Brian had known—a city of opportunity, commerce, and global influence—became a place of restriction and uncertainty.

The world Brian Thuan Luu once knew was shattered, but in 1979, he decided to fracture their family even further.

“My dad decided to send some of us out because he couldn’t afford to send everyone,” Brian, who was the second youngest of nine and put his hand up to go, recalls.

His older siblings boarded a large cargo ship one by one, leaving behind everything they had ever known. Eventually, it would be his turn. Freedom, however, had a steep price—12 bars of gold per person. One bar was around $700 back then. So, 12 bars per person—that was a lot of money.

Brian’s eyes glaze with tears as he speaks of the memory that hit him the hardest.

“When my parents saw me off that night, I stepped onto the boat, turned around to look at them, and that’s when reality hit me,” he continues softly. “I thought, Oh my gosh, what have I done? I might never see them again. I almost collapsed, but it was too late to turn back. My mom was crying, and I felt so guilty for all the times I had made them mad.”

After the boat finally dislodged from the coral reef, Brian, still a child, drifted through the Filipino refugee camp seeking information about anyone who might be able to lead him to his relatives. The burden of survival fell entirely on his young shoulders. With no family to look after him, Brian leaned on something unexpected: music.

“I played the guitar and performed in a band in Vietnam,” he says. “At nine years old, the local authorities used my brother and me to perform for them. That helped us stay under the radar.”

In the refugee camp, his talent once again became his saving grace.

“Since I played music, I performed here and there. A lot of families wanted to adopt me,” he says with a smile.

Yet fifteen months passed before Brian’s path to America opened up.

“At the camp, I wrote letters to refugee camps all over—Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines, Hong Kong—until I found my brother and sister in another camp in the Philippines,” he recounted. “And we were told we were going to America.”

Coming to America

Brian had already endured the impossible—war, escape, and the uncertainty of a refugee camp. But stepping onto American soil, he realized a different kind of challenge lay ahead. The question loomed: Could he ever truly belong?

Hope arrived in an unexpected form—a Jewish synagogue in Long Island, New York, that agreed to sponsor Brian and his siblings, giving them a foothold in a new world. “When we first arrived, we stayed with our sponsors for a month in Long Island,” he recalls. “My younger sister and I went to school while my older siblings worked. My brother worked in a factory making valves for airplanes, and my sister worked at Publishers Clearing House. After a month, our sponsors helped us find an apartment, so we moved but stayed in Long Island.”

But the road to belonging wasn’t always smooth. Language barriers turned simple conversations into uphill battles, and cultural differences made him feel like an outsider. And then there was the bullying. “Yeah, I was bullied,” Brian admits with a chuckle. “The funny thing is, kids would ask me if I knew Bruce Lee. I said, ‘Yeah, I know Bruce Lee.’ They asked if I knew Kung Fu, and even though I didn’t, I told them I did. I did a few moves, and they left me alone. Back in the ’80s, people were terrified of anyone who knew Kung Fu.”

Determined to carve out a future, Brian pursued his education at SUNY Albany, where he found an unexpected friendship with Scott Burns, a friend who urged him to share his extraordinary journey. He took that encouragement to heart, carrying his experiences forward into the professional world.

His career began in the quiet hum of late-night data processing at Far East National Bank in Los Angeles. “I worked the graveyard shift in the computer department,” Brian says. It wasn’t glamorous, but the unusual hours allowed him free time during the day to explore other opportunities. After five years, the family called him back to Queens, New York, where he secured a position at Great Eastern Bank. Life, however, had a few surprises in store—weekend gigs as a musician at Universal Studios in Flushing turned out to be more than just a side hustle.

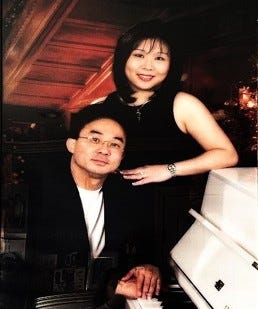

Then, in December 1998, everything changed. At an event at the Sheraton Hotel in Flushing, Brian met Jennifer.

“Six months later, we were married,” he says simply as if destiny had planned it all along. Kind and unwaveringly supportive, Jennifer wasn’t just his wife—she was his partner in life and business. She encouraged him to join World Financial Group, a company that secured financial futures and empowered individuals to build their own success. Together, they built a thriving career that gave them financial freedom, the ability to travel the world, and a peaceful home on the waterfront in Long Island.

Yet, through all the change, one thing remained constant—Brian’s love for music. He turned his passion into something bigger, founding Brian Luu’s Corp., a premier MC/DJ and event production company. With professional sound, dazzling lights, and an eye for unforgettable moments, he transformed celebrations into memories that lasted a lifetime.

From a refugee boat to a stage lit up with music and laughter, Brian’s journey was never just about survival—it was about reinvention. He had found his place in the world, not by leaving his past behind, but by carrying it with him, note by note, story by story.

“Here was I, someone who had only had a few years of school under the old regime before the Communists took over,” Brian remembered. “Yet when I came to America, I was lucky because my high school had what they called the TESL program—Teaching English as a Second Language. It was a program for all foreign and immigrant students, and I was part of it.”

Yet it wasn’t until he took the oath at his citizenship ceremony in 1986 that Brian truly felt like an American.

“I was 19. That was when I finally felt like an American because I had been through so much just to become a U.S. citizen,” he says with a smile. “It was like going through hell and back. But after taking that oath, I gained a sense of confidence and self-esteem.”

Vietnam Today

Nearly fifty years after the Fall of Saigon, its impact still reverberates across generations. For those who lived through it, the memories of loss, displacement, and survival remain vivid, shaping their identities and the way they see the world.

The event marked not just the end of a war but the beginning of a vast Vietnamese diaspora—families torn apart, lives rebuilt in foreign lands, and a culture forced to straddle past and present. For the children and grandchildren of refugees, the legacy of Saigon’s fall is carried in stories of resilience and sacrifice, a reminder of the fragility of freedom and the cost of war.

Even now, as Vietnam moves forward into one of the planet’s leading economic hubs, the scars of April 30, 1975, remain etched in history—a testament to both the endurance of a people and the lessons that should never be forgotten. For the likes of Brian, however, this defining moment of history altered his life, wedging open the unexpected opportunity to forge a new path in a very new world.

“My wife helped me find about 608 Vietnam Veterans Associations. I sent thank-you letters to each of them, and 10 people have already responded,” he tells me enthusiastically.

FOR EXCLUSIVE GLOBAL CONTENT AND DIRECT MESSAGING, PLEASE CONSIDER A PAID SUBSCRIPTION TO THIS SUBSTACK TO HELP KEEP INDEPENDENT, AGENDA-FREE WRITING AND JOURNALISM ALIVE. THANK YOU SO MUCH FOR YOUR SUPPORT.

For speaking queries please contact meta@metaspeakers.org

For ghostwriting, personalized mentoring or other writing/work-related queries please contact hollie@holliemckay.com

Follow me on Instagram and Twitter for more updates

I supported Vietnam during the War Not the Occupying Yankees in Vietnam !