Dispatch from Afghanistan: Inside the deadly terrorist attack that killed dozens of Afghan school girls... “We can come out of our home at our own will. But we are not sure if we are going to return.”

“Never mind any of those things. Because history isn't easy to overcome. Neither is religion. In the end, I was a Pashtun and he was a Hazara, I was Sunni and he was Shi'a, and nothing was ever going to change that. Nothing.”

― Khaled Hosseini, The Kite Runner

KABUL, Afghanistan – It is the most searing scene: Hazara girls sitting hunched over on the broken earth, weeping so hard in each other’s arms that they cannot speak, their cries echoing like howls through the dusty alleyway.

Two days earlier, in the early hours of Friday, September 30, an unfathomable terrorist attack struck the already intensely persecuted Shia Hazara minority. A suicide bomber exploded on packed classrooms tucked inside the Kaaj Educational Center in the Hazara-dominant Dashti Barchi neighborhood of western Kabul, where hundreds of gender-segregated students – mostly girls and some boys aged between 17 and 20 – were preparing for university entrance exams.

The suicide assailant, the surviving students tell me afterward, detonated in the women’s section of the exam hall. Women are always soft targets in conflict. The death toll stands at at least 53 dead. But with dozens more gravely wounded, the figure rises with each passing day.

“There will be many more than 50 killed. I don’t know the exact figure, but I am witness it. There were many more killed. As soon as they (attackers) entered, many were shot by the gun only,” Basira, with a tough, small voice, tells me. “I was in the next class, next to the main one. There were 18 students. As soon as we heard the gunfire, we locked the door on the inside so they couldn’t come in.”

She unravels her traumatic tale in staccato as if talking about a life that belonged to someone else.

“Then when the blast happened, all the mirrors were broken,” Basira recounts. “The pieces would fall on our heads, and we were waiting (to die). It makes you feel hopeless. We were calling our families, letting them know that this happened. We even told them goodbye.”

However, the young woman with eyes rimmed from exhaustion was one of the lucky ones.

“We waited there for five to eight minutes. Finally, out of 18 girls, only five were left in the room, and the rest ran out into the yard to run away, and since then, they have disappeared,” Basira continues. “Later, we came out of the class and ran toward the wall, and the boys helped us get out.”

A small pool of survivors gathers around me, all girls and women aged between seventeen and twenty who weathered the blast. Each one lost a relative or a close friend, and each one is waiting to lose someone else they loved most in the world as the death count ascends.

“My memories aren’t cleaned up. I can’t eat,” another girl, trembling, whispers. “I have no appetite for anything.”

They vividly detail how they raced for their lives to the back of the yard, where the Hazara boys – covered in blood from both their own injuries and the wounds of others – lined up plastic chairs to help the girls lift themselves over the concrete wall and away from the carnage.

Yet contrary to what has been reported, the barbaric attack was not the work of just one suicide bomber but a carefully coordinated team. One survivor, Zarmina, says there were at least three attackers that she saw with her own eyes.

“First, they (two) came here and shot the security guard, and then they opened fire at the students in the class,” she recalls, her voice cracking with emotion. “Then, once everyone started running, there was the suicide blast.”

It remains unclear if the two alleged gunmen escaped.

I notice an especially petite, fine-boned beauty wrapped in the dark colors of mourning shaking beside me. In a gentle, sing-song voice, she explains her name is Jameela. It takes her a long time to reveal that she lost her baby sister Laiqa, 18, in the madness, that her mother had sent her two daughters from their home province of Maiden-Wardak to have the opportunity to sit the university exam.

“I came late to class and got a seat in the last part of the class, just before the boys,” Jameela says painfully.

It was a minor infraction that would save her life.

“My sister came earlier, and that is why she was in the front row,” Jameela continues as if trying to steady herself before shattering into a million pieces. “I don’t know what happened to her, but we were told to wait there when the first two bullets were fired. Only then they entered and started attacking, and everyone was running away.”

Her face creases with myriad emotions, from anguish to anger to utter depression and disbelief.

“I don’t know what happened to her, but when I was able to look over, I saw that her face was burned. I recognized her only by her scarf,” Jameela says of her sister, who dreamed of one day becoming an engineer. “We were sent here by our family, and they never said send us one of you back in a coffin. So only my mother is left, and she is in trauma; she has no control over herself. My father is dead.”

So far, no one has claimed responsibility for the heinous attack. However, the Afghan branch of the global terror outfit Islamic State – known as ISIS-K – has persistently carried out horrific attacks on the embattled Hazaras, blowing up their hospitals, schools and mosques.

“The attack on civilian places shows weakness and hostility toward the people of our country,” Abdul Nafi Takoor, the Taliban spokesman for the Interior Ministry, said in a statement.

While the Taliban, during their first reign of power in the years before the U.S. invasion after September 11, was broadly accused of persecuting the Hazaras, the re-emerged Emirate has pledged to protect them this time. However, such a pledge seems fleeting and flimsy to those in the line of the fire.

“We need more security. With the current condition, who knows what will happen to us,” Aman, a 53-year-old Hazara, says, as if pleading for his words to be heard. “If the protection were there, the blast would not have happened.”

More distressed faces emerge from the crowd.

“The Taliban was 150 meters away from here when the bullets were fired. So they should have understood to come here fast,” another survivor, Zahra, informs me wincingly.

Some Hazaras lament that they were being laughed at in their darkest moments, an insult to the inflamed injury.

It is all a painful pill to swallow. The war is supposed to be over. But perhaps it is only over for the U.S. In reality, the growing deluge of attacks the minority faces each day illuminates the struggle for security still gripping the impoverished country and the nagging fear that still clings to the still and heavy air.

“They don’t treat us as humans,” Mahtab, another student, says.

Hazaras are broadly considered Afghanistan’s most discriminated ethnic minority group and, for centuries, have stared down the barrel of intense violence and discrimination in the Sunni-majority country. In the late 19th century, Hazaras were assembled under the Abdur Rahman Khan Pashtun reign – thousands of men slain so their lands could be seized, and thousands more women abducted as slaves.

Despite the abolishment of enslavement by King Amanullah Khan in 1923, the past century has been rife with Hazara targeting and the amplification of their persecution politically, economically and socially.

Throughout the two-decade U.S. occupation, Hazaras were (at least on paper) included in a small number of government positions. Yet, structural prejudice continued in public sector jobs and in the allotment of foreign assistance and national budgets. Moreover, their ability to speak out and protest their hardships was further hamstrung by systematic violence and bombings at their community demonstrations.

But the seemingly ingrained hatred extends far beyond their religious identity. Hazaras are widely known for their whimsical literary customs and disparate breed of folk music steeped in sonant traditions of poetry and storytelling. Hazara women also typically experience more freedoms than many of their Afghan counterparts in the way they dress, exposure to education and the types of vocations they pursue, all of which hang in limbo as a result of the Taliban’s rebound to the throne.

CLICK TO READ MORE IN THE DALLAS MORNING NEWS

I am surprised to see an out-of-place face in the small Hazara crowd mourning outside the charred learning institution. A young man with glasses and a thick shock of curls introduces himself as Hamid, a 19-year-old Pashtun artist and writer who has come to show solidarity with the hurting community. It is a tiny, albeit significant flicker of promise in a bleak landscape.

“I want to talk to the people. I want to help them. It’s not just the pain of the Hazara community; it is the pain of all of Afghanistan. As a Pashtun myself, I am here to share the pain,” Hamid asserts. “Today is their day, and the next day is ours. I fight for the unity of the ethnicities to make one nation. I have worked my best to make all people come together and start with Hazara.”

I overhear the Taliban soldiers arguing with the determined, heartbroken Hazara women.

“You didn’t inform us you were having a gathering at the institution. Whenever a group comes together, authorities should inform us so we can coordinate with the leaders in the area,” one young Talib tells the distraught women. “But they didn’t tell us anything. In the last year, you have never told us anything.”

An Emirate spokesperson argues that the government has taken the “necessary measures” to safeguard the minority, insisting that all Afghans are equal in the law and there is no discrimination.

I turn to the Taliban on the ground at Kaaj, hoping to include their perspective and rundown of what happened. Instead, a Taliban member yells viciously at me after the Hazara girls ask me to take a photo with them, demanding I hand over my phone. I refuse. Taliban soldiers then escort me to the nearby police station, insisting I do not have permission to be there and to talk to the traumatized community.

The matter is quickly resolved once the local commander sees my permission letters from the Foreign Ministry and Kabul’s Information and Culture Director. Then, I return to the learning center, where working feels like I am walking on eggshells around a crime scene, wrapped in suffering and frustration.

What is especially searing about the Kaaj onslaught is its blatant assault on education, and girls’ education at that. The day after the onslaught, the survivors were back outside marching with signs to “stop the Hazara genocide” and demanding their full spectrum of rights and protection, before bullets cracked the air and the demonstration was dismantled.

Still, the girls line up outside the still-shuttered school days after the tragedy, their arms filled with textbooks. I admire the way they wait persistently in the harsh midday sunshine, demanding to be let inside, desperate for the opportunity to learn. Education, something so many of us takes for granted, is profoundly cherished by the hurting Hazara.

“Nobody can take us away from education. We come here just to show that the more they (terrorists) try to kill us, the more we will keep coming to study,” Basira explains, her voice gaining momentum. “We are not going to sit back. The more you kill us, it doesn’t matter. We will continue our education because we hope for the future. And we believe the future will be bright for us.”

The issue of girls’ education in Afghanistan remains a fraught one. Most provinces still do not allow secondary girls to attend public school classes; however, university tuition is permitted.

After some arguing, some pleading with the Taliban in their quest to at least be able to learn from home, two wailing girls are eventually granted permission to enter the blistered building to collect their books and materials. Their tiny hands entwined. I have never seen humans run so fast.

“Our message to the world is that we can come out of our home at our own will,” Jameela says gently. “But we are not sure if we are going to return.”

It seems to me that many Hazaras live their lives on luck and the fading belief that someday, someone will hear them and put a miraculous stop to the bleeding.

“Give us protection, or the United Nations should hear us and do something. We are tired of it,” Jameela adds. “(The Taliban) should either provide protection for us or let us do it ourselves, and they should just go away from the area.”

Maiwand Naweed contributed to this report

CLICK TO READ MORE IN THE LIBERTY DISPATCH

CLICK TO READ MORE ABOUT LIBERTY’S SUPPORT FOR VETERANS

Please follow and support my investigative/adventure/war zone work for LIBERTY DISPATCHES here: https://dispatch.libertyblockchain.com/author/holliemckay/

For speaking enquires please contact meta@metaspeakers.org

Pre-order your copy of “Afghanistan: The End of the US Footprint and the Rise of the Taliban Rule” due out this fall.

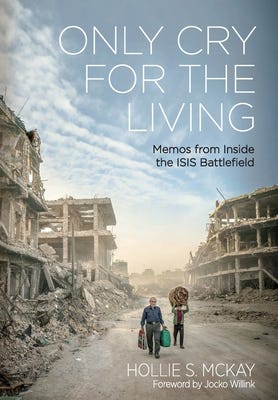

For those interested in learning more about the aftermath of war, please pick up a copy of my book “Only Cry for the Living: Memos from Inside the ISIS Battlefield.”

If you want to support small businesses: