“Right now, this life cannot be called a life. But somehow we are forced to live it.”

- Asyeah Jasoor, 22

It’s been a year since the US finally withdrew from Afghanistan on Aug. 30 after occupying the country for more than two decades. The Biden administration’s hasty removal of US troops led to chaotic scenes at Kabul’s international airport, with Afghans clamoring to leave before the Taliban took over. At least 170 people and 13 American service members were killed by twin ISIS-K suicide bombs at the airport’s gates.

And while more than 100,000 Afghans were airlifted out of the country, it is believed that up to 80,000 Afghan allies who worked in some capacity to support the US mission are still left in limbo.

Now, for the millions of women and girls left behind, the place no longer feels like home. Their nation has been plunged into antiquity, back to a time when women were relegated to a dank basement, their faces buried beneath a sea of burqas. In May, the Vice and Virtue Ministry of the Taliban ordered all women in the country to cover themselves head to toe, including female TV news anchors.

Taliban leaders have also banned girls from going to school beyond grade six. Although they say they believe in women’s rights and want to return girls to education, they claim they must first ensure that females are transported to school separately and safely from males, and appropriate uniform policies are established. None of this has happened yet.

Courtesy Jake Simkin

Women who had once led dynamic lives in public institutions have disappeared from view. Dreams of reaching the top echelons of business, sports and education have vanished, replaced by the fundamental struggle to survive day after day.

During the day, women can still roam around — although many choose not to — and they are forbidden from traveling to “faraway places,” typically considered more than 45 miles from their home, without male supervision.

One Afghan woman described it to me as “living under the law of the jungle.”

According to the UN’s World Food Program (WFP), 75% of Afghans spend what little money they have on food, and more than 80% of families are in debt. Afghanistan’s economy, which had been almost entirely supported by foreign aid during the occupation, immediately collapsed once the final cadre of American troops departed.

Meanwhile, it is estimated that up to 90% of the more than 2,000 health clinics that existed before the fall have closed due to a lack of funding and operational challenges, leaving just a small number to serve the country of 39 million. After a June earthquake killed 1,000 people near Kabul, Afghanistan did not even have enough medical supplies to treat the thousands of injured.

This fall, Jake and I are releasing the coffee table book “Afghanistan: The End of the US Footprint and the Rise of the Taliban Rule” with Di Angelo Publications. It truly is a labor of love for both of us to capture the ups and downs of Afghan life before, during and after the fall last summer. PRE-ORDER YOUR COPY NOW.

Here is a book excerpt of the fall…

The body never lies. I rise early that Saturday morning, a strangely sobbing mess. The tears brace me for something I do not yet know.

Jake and I meander slowly through the oddly empty Mazar. The city’s dynamism is stripped into shuttered stalls, as hundreds line up outside the banks to withdraw whatever cash they can in a last-ditch bid to head somewhere else.

There is no longer a way out for us. We are booked on the earliest commercial flight back to Kabul, but that is not until Monday evening.

Frightened families are stuffing themselves along with bags of belongings into tiny, intricately colored rickshaws and retreating into the city center, their homes on the periphery under threat. Shops are sealed closed, and cars and construction equipment lie abandoned beneath the scorching sun.

Around midday, Jake and I climb into a random cab and drive toward what we presume to be sandbagged frontlines and Afghan and resistance forces putting up the fight of their lives. But there are no fights to be seen nor heard.

“I’m scared,” the cab driver unexpectedly croaks out.

Our interpreter, Hami, still on his Nokia flip phone on a call to a friend, turns to us in the backseat.

“The Taliban has just broken through the first of the three frontlines,” he blurts out with a bizarre smile, either out of secret pleasure or simply to appease my unease. “We are surrounded.”

I assuage my discomfort by working holed up in the hotel room for that long afternoon, stupidly assuring myself that the city will hold until I can fly out in forty-eight hours. Driving is an impossibility; the Taliban has long controlled critical thoroughfares over much of the country.

Jake and I step out into the haunting blackness of deserted streets that evening. We sit nervously at our regular kebab café, inserted down a dozen asymmetrical steps beneath a spice store. For a little while, we pretend it isn't strange that the cords for the television have been yanked from the wall and that no one else is inside.

Before long, the innate anxiety that prickles your skin and shivers your spine becomes too much to tolerate. We forgo chunks of meat and yogurt and hurry across cracked pavements, through the emptiness toward our towering hotel blocks away.

As I step into the apparent safety of the hotel, pivoting around to take in the surreal scene, I notice a cluster of men on motorcycles, in traditional shalwar kameez dress with austere hairy faces, storming into the silence.

That is the Taliban.

Celebratory gunfire echoes through the starless night as we watch from the top floor, moving away from the glass walls as a precaution.

“It’s falling,” I text anxiously to a good friend.

An email alerts me that Monday’s flight is canceled.

“It is fallen,” I text again.

There was no fight, no all-out endeavor to hold on.

And just like that, we say a silent goodbye to the Afghanistan we had grown to know and embrace. From the window of my hotel room, unclear how the Taliban will treat foreigners, journalists, a woman, Jake and I set about plotting how we are going to safely exit.

Throughout that first aberrant night, I curl up in a fetal position on the floor so no one can see me and text with another Afghan friend in Kabul, Sama. She is nineteen, studying pharmacy at university with aspirations of becoming a doctor. Sama knew nothing of her country before Americans came in.

“I don’t know what any of this means,” she writes over and over again.

CLICK TO READ MORE IN THE LIBERTY DISPATCH

CLICK TO READ MORE ABOUT LIBERTY’S SUPPORT FOR VETERANS

Please follow and support my investigative/adventure/war zone work for LIBERTY DISPATCHES here: https://dispatch.libertyblockchain.com/author/holliemckay/

For speaking enquires please contact meta@metaspeakers.org

Pre-order your copy of “Afghanistan: The End of the US Footprint and the Rise of the Taliban Rule” due out this fall.

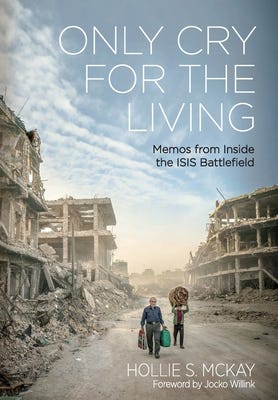

For those interested in learning more about the aftermath of war, please pick up a copy of my book “Only Cry for the Living: Memos from Inside the ISIS Battlefield.”

If you want to support small businesses: