“Light will someday split you open; even if your life is now a cage.”

― Hafiz

This week we traveled through Nangarhar, Kunar and the mysterious, hard-to-reach province of Nuristan. It truly is the land of light peppered with frozen hilltops and curious, kind faces emerging from the thick and untamed terrain.

Indeed, getting there was no easy feat – entailing hours of spluttering through rocky mountain tracks, some steeped in snow and all of it coated in the unknown.

My favorite moment in the off-grid adventure happened as we were hiking through the valley, littered with rare earth, when the young gemstone miners in the cave started dynamiting the rock above, triggering us to bolt for cover. But in the end, when my heart rate went back down a touch, they spotted us and invited us up into the fascinating little home mining operation and then to their one-room wooden home in the mountains for tea.

Afghans are genuinely hospitable people. The men poured us little bowls of popcorn from their backpacks and found us peanuts to shell as they talked about their lives, the coming winter, the challenges embedded in their beleaguered country.

On my travels, I’m also reminded of the degree to which Afghans bear the physical wounds of war with no reprieve. So many have lost limbs, rendering them ever more entangled in the struggle to survive, unable to work or take on physical labor jobs. There are no government handouts.

Moreover, the Afghan economy is already sliding into crushing despair. With winter sweeping in and next to no NGO support compared to what previously existed, my heart goes out to those suffering the jarring physical manifestations of what conflict does to combatants and civilians alike. As a Kabul-based doctor told me weeks ago, those from poor families who become disabled are sometimes deemed a burden on their families as everyone is battling to find enough food and shelter to survive another day.

“If they step on a landmine or something,” the doctor whispered sadly. “It is just better often for some families if they die.”

This young man approached us in Nuristan for help. He was shot in the hand by a stray bullet; and was struggling to find work and feed his family. I recognized the tremendous challenge that comes in asking for help in a land embedded on the pillars of pride and dignity. I am also in awe of those who can smile through such hardships, and the resilience that stems from understanding that this too shall pass. Somehow.

I am also aghast more and more each day regarding the level of corruption that infected this beautiful country and the decisive role it played in the Taliban coming back into power. I can only hope the U.S and other countries that entered the Afghan war theater learn from the wincing past two decades that corruption lingers at the root of extremism recruitment.

In many ways, it was the fraud that opened the floodgates to the Taliban. Multiple military insiders stressed to me that the level of corruption swelled throughout 2021 when it became clear that the United States was on its way out, with the Taliban able to pay off troops of all echelons for information and insider attacks.

But long before that, cash flooded the country and into the hands of corrupt officials and their friends and family, with the U.S. taxpayer essentially funding projects that never got off the ground or eroded in a season or two.

Most of this money flow seemingly drifted unchecked and with little accountability, providing the Taliban with the perfect recruiting tool for disaffected and frustrated Afghans to pounce upon.

LIFE TODAY INSIDE A TALIBAN TRAINING CAMP

At first glance; it appears a region so remote – set upon lush, streaming valleys without roads and unreachable by regular vehicles – that it must have been untouched by the decades of brutal conflict that masticated much of Afghanistan.

But delve a little deeper into the archaic clay homes, the faded color of walnut, set on the foothills above the lush and overgrown streams and hints of something slightly sinister start to emerge.

We weave into the tiny, six-family village of Yaw Dean, meaning “One Religion” in Pashto, tucked deep into Logar’s Khushi district, inside the town of Do Bandi. Residents say they have always been under the control of the Taliban – even throughout the past two decades of crisis and conflict.

“This area has never been under the government’s control. They only had a few checkpoints on top of the mountains, and they would sometimes try to enter the village with full force. Still, they never got to control here,” affirms Jannat Gul, 34, who is known as Engineer Mosaddiq within the Taliban, and now works in Logar’s Public Health Commission.

A collection of crumbling, stone dwellings spread over a small mountain for decades are filled with secrets. Now abandoned, those bunkers and dusty tracks curling toward the hilltops not so long ago served as the sinister training ground for the Taliban’s contingency of suicide bombers.

“One-hundred-fifty (Taliban) soldiers lived here. So they created a bunker to hide,” Gul continues, motioning to rectangular apertures in the mudbrick caves. “In this area, we had our suicide bombing vests, and we trained suicide bombers here. So we had 150 people ready to commit a suicide bombing.”

However, at some point during the intense fighting, the Taliban top-brass received word that the area would be bombarded; thus, the insurgent fighters fled – leaving their explosive ordinance devices behind to detonate upon Afghan soldiers.

Throughout its decades-long insurgency, the Taliban unleashed scores of deadly suicide attacks targeting the Afghan government and NATO forces, with countless civilians caught in the crossfire. According to many Taliban commanders I have interviewed over the past week, such training will continue across Afghanistan despite their rise in power – ready to go should another group or country ever purport to interfere on their soil.

It’s a patch of existence so removed from the bustle – while only forty jagged miles from Kabul – that there are no longer holes in the earth used for squat toilets, no semblance of showers or internet and connection with the world outside the dun mountainside. Even the Talib fighters dotting the area at first wonder if I am a man, the idea of a woman outside working strikingly unfathomable.

“Most of Taliban’s family members live in this village. From each house, at least one member either the father, brother, or son part of the Taliban regime,” Gul explains, as to why the government could never get a grasp of the quaint, timeless place.

Splutter through the streams a little further, and a spattering of primordial hut homes idle in the late afternoon light, projecting a gloom across the expansive terrain.

Small children with matted straw hair, rotting teeth, and eyelashes lathered in dust roam barefoot on the cold earth, wrapped in thin, colorful clothes hardly fitting for the perpetual winter chill in the isolated carton of the world. One small boy seems to have found a Santa Claus hat that he uses as some token of protection for his ears, cleaved by frost.

There are no women in sight. For the most part, women marry young and only surface again into the somewhat public sphere in old age.

It is parcel some outsiders have ventured through – although never stopping. Its haunting isolation and lack of government control over the years have made the secluded village a key smuggling route for cash-strapped Afghans. Everything from weapons and wood to opium, cannabis and cars apparently move through the willowy spot, mainly to Kabul and Laghman, or to Paktia and then potentially into Pakistan.

While their day-to-day life has not changed regarding the new government, the baggage of the financial hardship is hitting home. The primary sources of income have long been agriculture and the selling of wood.

CLICK TO READ MORE ABOUT THE TERROR TRAINING CAMPS IN LOGAR

BEHIND A BILLBOARD OF BOWE BERGDAHL, KHOST MAINTAINS ANTI-TALIBAN WAYS

It’s one of few stretches of road among these winding hills and twisting valleys that remains paved and intact, untouched by the two-decade war that crippled most of Afghanistan’s land arteries. But the road from Kabul to Khost — 150 miles by way of Logar and Paktika — is a serene drive through a lush and primitive landscape tucked inside the bloodstained land. Yet the province of 650,000 comes with a chilling history. It’s home to much of the Haqqani family, and this thoroughfare was long used for al Qaeda and Taliban operatives to trundle in and out of the Pakistani tribal region of Waziristan, where extremist madrassas and training camps have flourished.

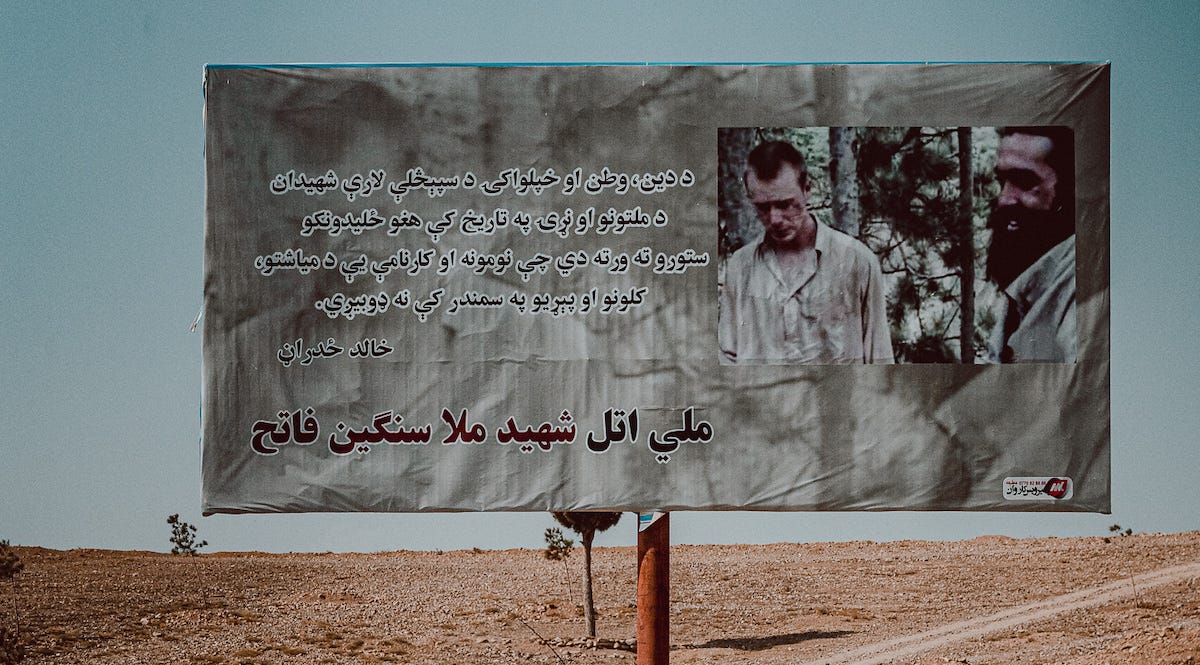

On a dusty field in the city of Khost, a giant billboard lit by fall sunshine caught my eye.

It features Bowe Bergdahl, the US Army soldier who deserted his post in the neighboring province of Paktika and was ultimately held captive by the Taliban-affiliated Haqqani Network from 2009 to 2014. He was released on May 31, 2014, as part of a prisoner exchange for five high-ranking Taliban members — one of whom is now the provincial governor — held at Guantanamo Bay.

“Martyrs of religion, country, and holy path are similar to shining stars of nations and world history whose names and actions can’t be drowned in monthly, annual, and decade oceans,” the Pashtun poem by Khalid Zadran reads alongside the picture of a distraught-looking Bergdahl and a smiling Mullah named Sangeen Fateh.

The Bergdahl billboard in Khost is less a celebration of the captured American than a tribute to Fateh, who was killed in 2013 by a US drone strike and is remembered as a favorite leader among the Haqqanis. In another busy spot in the city center, a billboard featuring Fateh reads, “Afghan Mujahed who closed the invading American soldier’s eyes and tied his hands and made the West realize the outcome of the invasion.”

As I walk the streets, though, none of the civilians I speak with really seem to know why the glaring billboard is there — even though the Khost governor is Mohammad Nabi Omari. He was one of the five men exchanged for Bergdahl.

CLICK TO READ MORE ABOUT THE ANTI-TALIBAN SENTIMENT IN KHOST

Other Upcoming Events

If you would like to listen to more Afghanistan observations please join the Atlantic Council panel happening this Wednesday October 27th. Register here.

Follow me on Instagram and Twitter for more updates

Photos courtesy of my brilliant photographer @JakeSimkinPhotos. Please consider a paid subscription to allow us to continue this work.