Mother's Day Series: The Jaw-Dropping Mothers of Darfur

Dispatches on Mothers in Crisis and Conflict

Dafur, Sudan

Widowed by violence and torn from their families, Darfurian women face more than just the loss of a spouse. Widowhood becomes a rugged reality of struggle, stigma, and silence, reshaping their lives as they navigate a fractured society with fatherless children.

The conflict in their Sudanese homeland has claimed thousands of lives, leaving countless women widowed. In West Darfur’s capital, El Geneina alone, over 5,000 civilians—primarily non-Arabs—were killed between April and June 2023. The exact numbers are unclear due to limited access and chaos on the ground, but the scale of the crisis is undeniable.

One late afternoon, in this place that feels like it teeters on the edges of the earth, where the sun still burns as it sinks and the view is cloaked in the debris of countless displaced lives, I sit on the ground with Fatimah and her young daughter, Madihh. We’re outside their provisional home, the walls of which are little more than tarps and sticks, and a thin plastic mat is spread in the sand beneath us. Tiny children peek through the gaps in the straw fence, their eyes wide with a mix of curiosity and wariness. The sounds of chickens pecking the dry ground are strangely comforting, a throwback to my own summers spent on my grandfather’s sugar cane farm in Australia’s far north, but they cannot drown out the silent heaviness that tacks itself onto everyone at every moment.

Fatimah, a woman of fifty-five, looks much older than her years. Her eyes, sinking with the heavy burden of her experiences, seem to nurse the pain of many lifetimes over. Beside her is her daughter Madihh, barely fourteen, whose small fingers grip the cotton of her dress.

“We lived in El Geneina, and we had a home, a community,” Fatimah begins. “They came for us—the RSF, the Sudanese forces. They came into our house…”

The group of fighters were looking for her brother, Gasin. Madihh, who speaks with her palms open toward the sky, pretended not to know who Gasin was and insisted this wasn’t their home. The men whipped Madihh’s tiny frame, over and over again. Still, she told them she did not know a Gasin. The men left, but another group returned a few minutes later. This mob wanted money, demanding that Fatimah give them money.

“I told them I had none, but then they searched me and found a few notes in my pocket,” Fatimah says, remembering the ensuing cane beating that came as punishment.

One soldier wanted water, yet when she handed it over, he tossed it into the air.

“I asked him why; I told him we don’t have much water,” Fatimah continues.

Then, an RSF fighter stormed into the home and, out of nowhere, fired bullets into this already fragile mother. As Fatimah speaks, I watch Madihh’s face, her eyes distant, as if trying to hold back the surge of vivid recollections. Memory is the magic that keeps them alive and the devil that stabs them awake and in slumber.

Fatimah lifts her dress to reveal an angry stampede of scars distorted across her calf. “The soldiers, they didn’t care. They just shot me twice. My daughter, Madihh, had to watch. I could feel the blood, but I couldn’t move. We couldn’t get help right away. We went to a school, a safe place, but I bled for ten hours before we could get to the hospital.”

The nightmare had barely begun. At the hospital, Fatimah learned that seven family members were shot dead by the RSF – including her brother and son.

“I couldn’t cry,” she says, her gaze distant. “I couldn’t. I knew if I cried, the RSF would ask me why. They would ask if I was sad because they killed my children and punish me more. So, I kept it inside. I asked Allah not to be angry with me. I couldn’t show them my pain in front of them.”

Madihh nods, her gaze fixed on the sunburned ground. I can see the pain in her young face, but it is mixed with something else—a fierce, protective strength that has replaced the innocence of a child. Fatimah’s eyes soften as she looks at her daughter, her hand gently resting on Madihh’s arm.

The bond between mother and daughter is palpable, but it is not just the bond of love. It is the bond of survival. In this refugee camp, survival is not guaranteed. It is a constant struggle, and the youngest, like Madihh, are often asked to step into roles that no child should have to. I frequently see this tiny teen doing chores, almost always with someone else’s child strapped to her back.

“Life in the camp is hard,” Fatimah says. “Because it is not, it can never be, your home. You just survive.”

FOR EXCLUSIVE GLOBAL CONTENT AND DIRECT MESSAGING, PLEASE CONSIDER A PAID SUBSCRIPTION TO THIS SUBSTACK TO HELP KEEP INDEPENDENT, AGENDA-FREE WRITING AND JOURNALISM ALIVE. THANK YOU SO MUCH FOR YOUR SUPPORT.

For speaking queries please contact meta@metaspeakers.org

For ghostwriting, personalized mentoring or other writing/work-related queries please contact hollie@holliemckay.com

Follow me on Instagram and Twitter for more updates

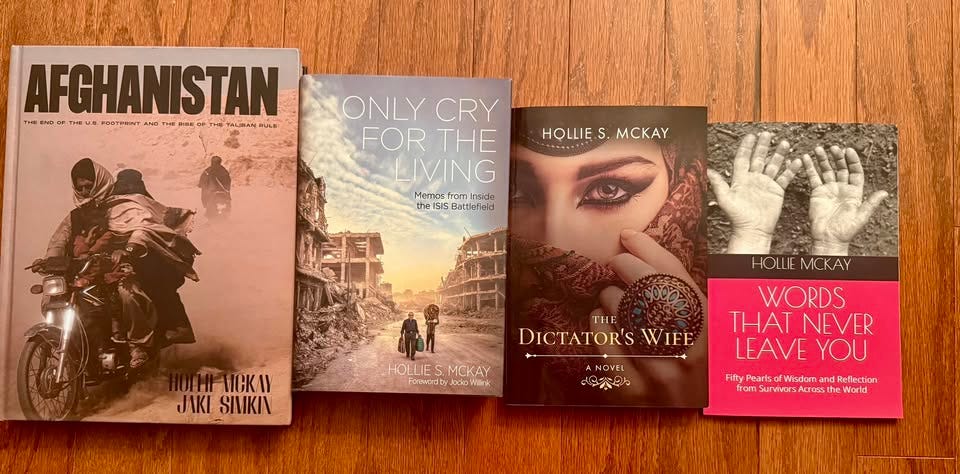

Click to Purchase All Books Here

Wow...

Thank you for helping us see.