Rebels Amputated the Limbs of Small Children in the Sierra Leone War – And Few Were Ever Held to Account

There are many reasons people choose to become journalists. For me, growing up, the story of Sierra Leone was one of them: unfathomable acts of cruelty followed by next to no accountability. It made me angry. It should make everybody angry.

The brutal decade-long civil war in Sierra Leone (1991-2002) remains etched in history for its horrific acts of violence. Among them, the systematic amputation of limbs, particularly those of children, stands as a chilling testament to the depths of human cruelty.

Sierra Leone, a West African country rich in diamonds, descended into chaos with the rise of the Revolutionary United Front (RUF), a dissident group that claimed to be fighting against corrupt diamond wealth, led by former student activist Foday Sankoh. Fueled by a desire for control of diamond mines and fueled by neighboring Liberia's civil war (1989-1999), the RUF launched a rebellion against the government. The conflict quickly devolved into a brutal struggle marked by ethnic violence and the targeting of civilians – including young children.

Child amputations were not random acts of violence; they were a deliberate tactic employed by the RUF. The RUF deliberately targeted children for several reasons. Amputations served as a horrific method of instilling fear. By attacking those seen as defenseless, the rebels aimed to crush the spirit of resistance and force communities into submission. This brutality wasn't just about immediate suffering; it also crippled the future. Taking away limbs meant children could no longer work and contribute to society, hindering the overall economy and making reconstruction even harder. Amputations could also be a twisted form of communication. Rebels might force victims to carry severed limbs as a warning or leave them with messages for the government or opposing forces.

The physical vulnerability created by amputation further served the RUF's goals of control. Children who couldn't care for themselves became easier to manipulate and exploit. The RUF might coerce them into becoming soldiers or force them into begging, further solidifying their grip on these vulnerable populations.

The exact number of child amputees remains unclear, with estimates ranging from 2,000 to 6,000. However, the psychological and physical scars they carry are undeniable. Children as young as five years old were targeted, with arms being the most commonly amputated limbs, followed by legs, hands, and feet. Many amputations were performed with crude tools, leading to severe infections and chronic pain. Beyond the physical challenges, these children faced immense social stigma and limited opportunities.

Sierra Leone continues to grapple with the long shadow cast by the war's use of child amputations. The social fabric of the nation bears the scars. Amputees, especially children, are often ostracized due to social stigma and a lack of disability awareness. This exclusion makes it difficult for them to access education and find employment, further marginalizing them within society.

The economic burden is another harsh reality. Prosthetic limbs, rehabilitation, and lost productivity due to disability take a significant toll on families and the nation's already strained resources.

Beyond the economic impact, the psychological trauma inflicted by the amputations, the surrounding violence, and the ongoing social stigma create lasting wounds for victims and their families. The national psyche is also profoundly affected. These horrific acts serve as a constant reminder of the war's brutality, fostering unease and hindering national healing and reconciliation efforts. Sierra Leone's path forward requires not only addressing the ongoing needs of amputees but also seeking justice and accountability for the atrocities committed.

And as an international community, we are doing a terrible job of holding perpetrators accountable once the dust has settled.

The Special Court for Sierra Leone, a joint effort between the UN and Sierra Leone established in 2002, was tasked with prosecuting war crimes and crimes against humanity. Charles Taylor, former Liberian president who fueled the conflict, received an 80-year sentence for aiding and abetting the RUF. However, many other RUF leaders, including Foday Sankoh, who died in custody in 2003, haven't been held fully accountable. The court's limited scope and challenges in gathering evidence also meant that not all perpetrators faced justice. The men who carried out those heinous orders got away with it.

These children – now grown – will likely never see any semblance of justice for what was done to them. I always say you can take a life without killing. And this is precisely what war does to the most vulnerable of all.

Somehow, we must do better.

PLEASE CONSIDER A PAID SUBSCRIPTION TO THIS SUBSTACK TO HELP KEEP INDEPENDENT, AGENDA-FREE WRITING AND JOURNALISM ALIVE. THANK YOU SO MUCH FOR YOUR SUPPORT.

For speaking queries please contact meta@metaspeakers.org

For ghostwriting, personalized mentoring or other writing/work-related queries please contact hollie@holliemckay.com

Follow me on Instagram and Twitter for more updates

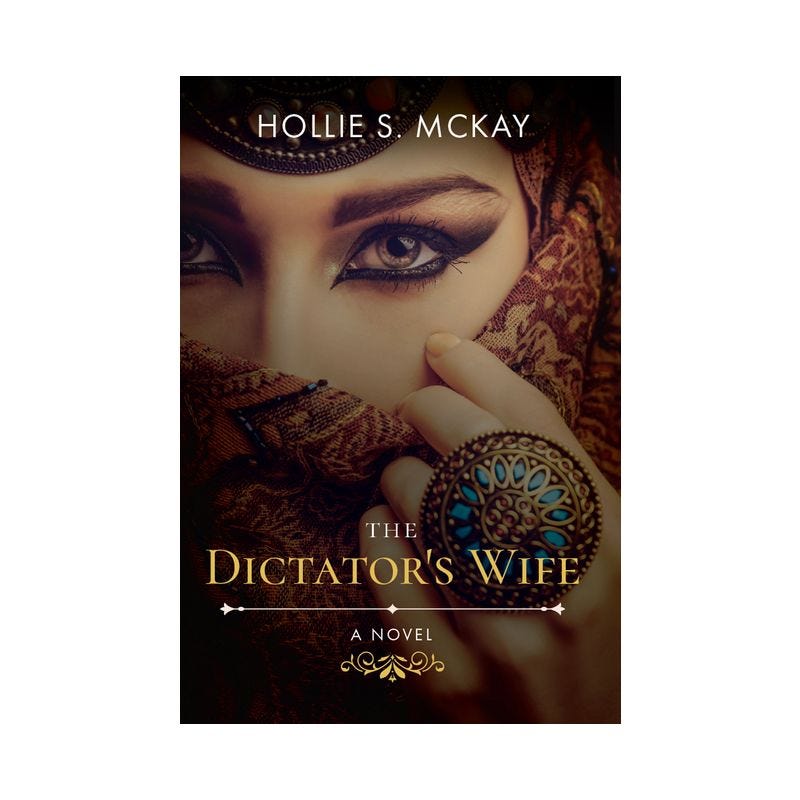

Order The Dictator’s Wife (out June 10)

Click Here to Order from my publisher DAP Publications (please support small business!)

Click to Purchase all Other Books Here

Holly, again you have shone on the spotlight on something I was unaware of. Do you know of any reputable charities that are helping these now young adults with their prosthetics or educational opportunities?