Saving Lives, Securing Influence: The Case for Americans Helping Others

USAID needs a clean up, but it should continue its important work

Life has come full circle for Archbishop Abraham Yel Nhial, who serves at the Aweil Diocese of the Episcopal Church of South Sudan. As a child, he was entangled in the brutal civil war in Sudan, forced to flee his home and travel on foot in search of safety, persistently under enemy fire from the predominantly Muslim population further north. Now, almost four decades later, the spiritual leader is devoted to helping the same people who dehumanized his family and fired bullets at him as a small boy.

Abraham’s resilience is a testament to the human spirit. His journey, marked by endless conflicts and chaos, is a source of inspiration. In 1983, a civil war erupted in Sudan, altering the lives of Sudanese boys and men. Government forces in the nation’s north fought against the southern insurgency, the Sudanese People’s Liberation Army (SPLA), forcing thousands of boys into its ranks.

The violence intensified in the late 1980s, driving more than 20,000 boys, some as young as six, away from their homes and families. The threat of being abducted or killed as a child soldier loomed heavy, prompting them to walk over 1,000 miles in search of safety. The journey was treacherous. Many drowned crossing Ethiopia’s bloated Gilo River. Others were slain by crocodiles or hippos. Thousands were shot dead by pursuing government soldiers. Those who survived became known as the “Lost Boys of Sudan.”

Dictator Omar Bashir surrounded the children at one point, hoping that they would die so that they could not grow to be soldiers. Archbishop Abraham and thousands of other children would have starved to death if it weren’t for the U. S’s leadership in the aid realm.

Let me be clear: I support a government cleanup, but let’s not eliminate important functions altogether. We are better than that. Our leaders can work to ensure that aid is effective and free from corruption. The foreign aid sector has had its share of fraud and inefficiency and should be audited and reformed. However, reforming aid is different from eliminating it altogether. Cutting off humanitarian support doesn’t stop waste; it just shifts suffering onto the most vulnerable.

In 2011, after a historic referendum, the predominantly Christian population of southern Sudan broke away from the north, forming the new nation of South Sudan. But the stability was short-lived. Ethnic violence exploded into yet another civil war, and for the past decade, South Sudan has been plagued by brutality and a staggering humanitarian crisis.

“People in crisis, when they see the U.S., they see the ones saving their lives,” Abraham tells me. “They saved us. If not for the aid, I would not be alive. The Lost Boys would have died of starvation.”

But now, Abraham is facing another crisis—one brought not by war but by a withdrawal of critical aid. Maternal hospitals in South Sudan, built with the support of USAID, are being shut down. And not gradually, but almost overnight. “They don’t say, ‘We’ll shut down in a year so you can prepare,’” Abraham says. “They say, ‘We’re shutting down in two or three weeks.’”

For the women of South Sudan, this is not just a crisis, it's a catastrophe. These hospitals are lifelines in a country where maternal mortality is among the highest in the world. Shutting them down means condemning women to suffer and die from preventable complications in childbirth. The urgency of this situation cannot be overstated.

Critics argue, “Why doesn’t someone else pay for it? Why does America have to?” But if the U.S. withdraws, that void will be filled—by China.

China is already making aggressive moves across Africa, especially in Sudan and South Sudan. Their approach is transactional. They extract resources, build subpar infrastructure, and hire workers rather than train locals. “They tell Africans, ‘Look, Americans don’t care about you,’ and then they bring in their own people. Sometimes, they even bring Chinese prisoners,” Abraham explains.

By contrast, the U.S. has long been seen as a force for good—not just because of its economic and military power but also because of its soft power. The humanitarian aid it provides, the schools and hospitals it builds, and the democratic values it promotes have long given America moral authority in the world. But withdrawing from places like South Sudan risks undermining that influence.

This isn’t just about altruism; it’s about strategic power. China is our adversary. And yet, we are handing over allies. If the U.S. stops showing up, others will step in. The choice isn’t between spending or saving money and maintaining or losing influence entirely. It's about strategic power and the future of global alliances.

Helping others matters if we want to be a powerful nation. While we should root out corruption, we should remember what matters.

Going forward, the Trump administration has a chance to get this right. The President says he is committed to peace. That promise must be honored by ensuring that aid programs, especially those focused on maternal health, remain intact. Humanitarian investment isn’t just charity—it’s strategy. It strengthens alliances, builds goodwill, and cements America’s position as a leader.

Beyond giving the gift of quality education in times of uncertainty and darkness, Abraham tirelessly mentors youth, bolsters orphanages, and offers shelter to children relegated to the streets. This vocation can never be finished. Even with thousands of lives saved, there will always be more in need.

Abraham still finds solace in the Bible in his moments of memory and pain. He is reminded of the central tenet that generosity yields an amazing crop. “As Luke 6:38 says, ‘Give, and it will be given to you,’” he tells me with a flashing smile. “As Christians, as humans, it is not enough to love your neighbor as yourself. You should want to love your enemies too and pray for your enemies.”

THANK YOU SO MUCH FOR YOUR SUPPORT. PLEASE CONSIDER A PAID SUBSCRIPTION TO KEEP INDIE JOURNALISM ALIVE.

For speaking queries please contact meta@metaspeakers.org

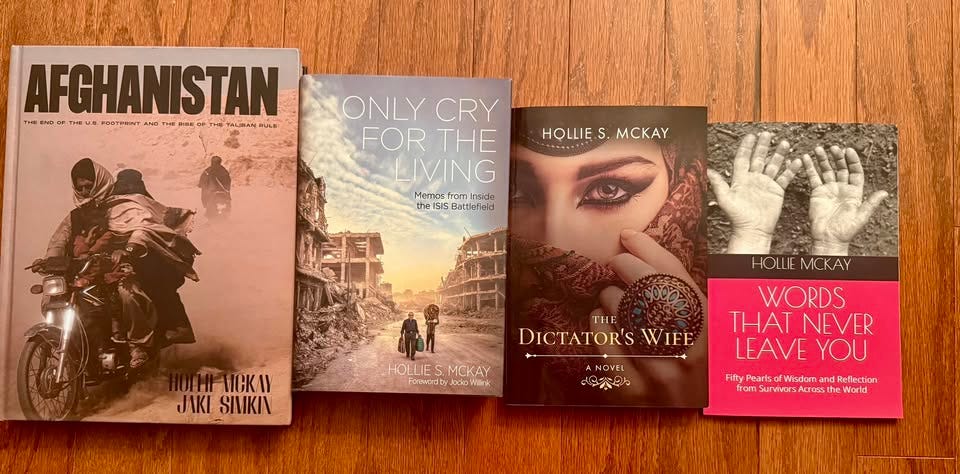

For ghostwriting, personalized mentoring or other writing/work-related queries please contact hollie@holliemckay.com

My best hopes and prayers for the people of Sudan, but I remember that I have a book on my shelves by Edgar O'Ballance called The Secret War in the Sudan, 1955-1972, reflecting how long this conflict has carried on during my lifetime. I fear it's roots and the pattern of conflict can be seen in even much older history.

“Helping others matters if we want to be a powerful nation. While we should root out corruption, we should remember what matters.”

The thing is why should we want to be a powerful nation? Why can’t we be a prosperous nation who cares for our own first, and then once our own are cared for, who can care for others out of our excess? Nobody tells Switzerland that they have a duty to be a powerful nation and thus must invest billions in foreign aide. Switzerland is just fine and somehow manages to wield a lot of soft power. Nobody tells the Scandanavian countries that they need to become powerful nations.

I see a solid argument for giving out of our excess, however we have a $1.83 trillion deficit and every thing the federal government is ostensibly supposed to do for the American people is under funded and falling apart. It is one thing to give from abundance, it is entirely different to be forced to sacrifice for others. It is deeply immoral to force the single mom in Chicago who got crappy maternal care in the U.S. to pay for maternal care in Sudan. It is wrong to force retirement age shop workers in rural America to pay for agricultural development in Africa (or anywhere else).

Americans in general have no responsibility to care for the rest of the world when they cannot care for their own. Nobody else is going to care for our poor. Europe isn’t going to give us infrastructure grants.

We murder a million babies a year in this country and have more than half a million homeless people on the streets yet running hospitals in Sudan is suppose to give us some sort of moral capital?

American Christians absolutely have a duty to support their brothers and sisters in Sudan, as do Christians throughout the world. We are not doing as well as we could in that regard. However it seems deeply unjust to claim that the average American owes something to the rest of the world so we can remain “powerful”.