When the drums of war begin to beat, the voices we hear first are not those who will soon find themselves in the line of fire. Politicians and generals declare the necessity of war, confident in their assessments from behind polished desks, far from the fields where bullets and bombs reign. The distance between those who decide on war and those who bear its burden is as much a physical gap as it is a moral chasm, and that gap has grown wide across history. In the United States, and around the world, those who send others into battle rarely taste the blood, fear, or pain that comes with combat. And yet, they continue to wield that power with a kind of detachment, trusting others to carry out the real cost of their decisions.

I have sat with veterans and soldiers in the United States and many countries around the world—men and women who were called upon to serve, often with little say in the matter. For many of them, war was not a choice; it was a duty they took up because they were needed. But as I listened to their stories of survival, of loss, of grappling with trauma long after returning home, I saw just how far removed they were from the decision-makers. These are not the stories of men and women who would so easily send others to fight. These are the stories of people who understand the brutality of war in a way that cannot be taught in a boardroom or debated in a political arena.

In the United States, those who declare war often come from an entirely different world than the men and women who carry it out. The ranks of our elected officials are rarely filled with people who know firsthand the life-altering realities of combat. Congress, which holds the power to declare war, is made up of people who, by and large, come from privileged backgrounds and hold college degrees. A small percentage have served in the military themselves, but for most, combat is an abstract concept—something they can rationalize as necessary without truly knowing what it means.

This divide is not unique to America. Around the world, we see political leaders from all backgrounds, many of whom have no personal stake in the wars they wage. Whether it is in the Middle East, Africa, or Asia, leaders send soldiers, most of whom come from working-class backgrounds, into conflicts. And while these politicians and diplomats discuss strategy in air-conditioned rooms, the soldiers they send endure harsh conditions, face an unknown enemy, and live each day under the constant threat of death.

There’s a fundamental difference in perspective that emerges when one’s life is at stake, and it’s a perspective missing from most high-level discussions of warfare. I’ve spoken to veterans who say that, once they’re on the ground, the geopolitical reasons for war fade away. In the chaos and violence, they’re no longer fighting for some grand ideology; they’re fighting to protect the person next to them. And when they return home, they bring back a complicated mixture of pride, trauma, and disillusionment, one that politicians rarely understand.

There is a troubling normalization of sending other people's children into war. For many political leaders, war has become a tool—a calculated risk, a bargaining chip, a show of strength. But for the soldiers who fight, war is never an abstraction. It is something they carry with them long after the final bullet is fired, long after the headlines have moved on. They live with the physical scars, the invisible wounds of PTSD, the loss of friends. Some never recover, and some never return.

This distance between decision-makers and combatants has even further-reaching consequences. In the United States, for example, the all-volunteer force means that only a fraction of the population serves in the military. Most Americans have little connection to the military; they’re removed from the realities of war, viewing it through screens and news cycles. This lack of shared experience makes it easier for the country to overlook the true costs of war, and it makes it easier for leaders to wage wars without public accountability. If the burdens of war were more evenly distributed, if more decision-makers had to send their own loved ones into combat, perhaps we would see fewer conflicts.

This disconnect is even clearer when you look at the resources provided to veterans after they return. Many soldiers come home with serious physical and mental health challenges, only to find themselves waiting months or years for adequate care. Despite their sacrifices, veterans are often left to navigate a system that feels indifferent to their needs. How can a nation that so readily sends its citizens into harm’s way fail them so profoundly when they return? And how can our leaders continue to make decisions to send more young men and women into battle, knowing how poorly we support those who come home?

The cost of war extends beyond the battlefield, seeping into families and communities. It’s the mother who loses a child, the spouse who spends sleepless nights worrying, the child who grows up without a parent. And yet, these are costs that decision-makers rarely consider in full. They speak of numbers and objectives, strategies and statistics. But for the rest of us, war is not a set of calculations—it is human lives, shattered and scarred.

We need to close this distance. We need a greater commitment to understanding the full impact of war before we send others into it. This might mean requiring leaders to spend time with veterans, or maybe even serving in the military themselves. But whatever the path, the decision to go to war should not be one made lightly or detachedly. It should be made with a clear, unflinching understanding of the costs, not just to the nation but to the individuals who fight.

If we could bridge this gap, if those who decide to go to war bore some part of its burden, perhaps we would see fewer wars. Perhaps we would find other ways to resolve our conflicts. Perhaps we could create a world where fewer people know the horrors of war firsthand, and where the distance between those who declare war and those who fight it finally begins to close.

FOR EXCLUSIVE GLOBAL CONTENT AND DIRECT MESSAGING, PLEASE CONSIDER A PAID SUBSCRIPTION TO THIS SUBSTACK TO HELP KEEP INDEPENDENT, AGENDA-FREE WRITING AND JOURNALISM ALIVE. THANK YOU SO MUCH FOR YOUR SUPPORT.

For speaking queries please contact meta@metaspeakers.org

For ghostwriting, personalized mentoring or other writing/work-related queries please contact hollie@holliemckay.com

Follow me on Instagram and Twitter for more updates

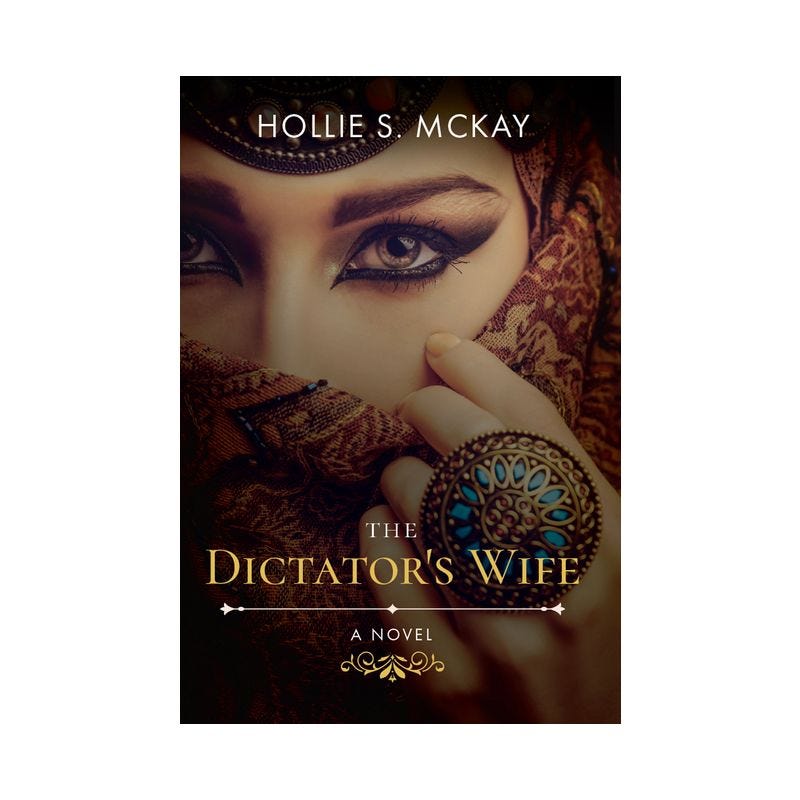

Order The Dictator’s Wife (out June 10)

Click Here to Order from my publisher DAP Publications (please support small business!)

Click to Purchase all Other Books Here

The awful, awful reality. Powerful piece, Hollie. 🙏🏻