The Life Before: How Ballet Led Me to War Reporting

There are more similiarities than you may realize

A walk down memory lane in rural Australia.

Around the age of four, my mother enrolls my sister and me in classical ballet lessons, disco dancing, jazz and tap. Then, there follow piano and elocution classes we call “speech and drama and effective speaking,” which require yearly examinations assessed by silver-haired men from England representing the prestigious Trinity College of London.

My parents were both very poor as children, and my mother makes sure her daughters have all the opportunities she never had. She was also lonely as an only child on a farm. Thus, she wants to ensure that there are no slivers of spare time that make her girls lonely.

“With the arts, you can never be lonely,” she sometimes said, tucking me beneath a soft quilt that would always burst at the seams and wake me with feathers tickling my nose.

Meanwhile, my father worries that we are being pushed too hard. He gets upset when he sees us in sequined tutus with cloth in our hair to form ringlets, our cheeks with chubby blush, and red lips like clowns in the town parade. Despite this, he still drives us across the country to contests, dodging bounding kangaroos on the dark and open roads, and tells me I should have won when I didn’t.

This definition of who I am has yet to sink in: I am a ballet lover seeking order and a place to belong and a tomboy with a carefree streak trying to turn the world upside down during lunch. Nobody really knows where to place me, but I do not want to be placed.

At nine, I convince my mother that piano lessons are a waste of money. After years of lessons, I know how to play little beyond “Ode to Joy.” I am instead fascinated by the inner workings, preferring to spend every thirty-minute class peering inside the colossal instrument, shrieking with delight as the hammers pop up as I press a key.

My mother cancels piano classes and instead enrolls me in more ballet classes. Almost every afternoon after school, we drive to the fringes of town to a crumbling, beautiful 19th-century manor—Skellatar House—wasted by the weight of time and neglect. It is haunted; something out of a “Goosebumps” novel. I dance until late into the night most nights, then frolic to the waiting car in my practice tutu and canvas shoes with undulating pink ribbons up my calf. I am sure something strange will tumble from the decaying verandah into the soul. I wait for it—the dead intrigue me more than they frighten me.

But over time, I protest the hours of learning steps with operatic French names. I’m always in trouble again, my hair pins flying into the shins of others because I have no idea how to do a proper bun. And this fixed routine of bar to the center to the curtesy at the end is growing boring. Rollerblading in the park, sleeping at friends’ houses on Fridays, and netball training on Wednesday nights seem thrilling and ordinary.

Neighborhood kids lead beautifully ordinary lives, and I want to be a child like them for just a moment. However, I am up early for a 7 am class, even on a Saturday. Mum says if I attend classes one more week, she will tell the teachers I won’t return. She keeps telling me this until I finally give up asking.

Above the cassette player in the studio is a small, faded sign. I have read it many times.

“Discipline turns talent into ability.”

I am about nine when it clicks. Really clicks. Why not be different? But most importantly, why be at home inside a lion’s den when you can float through classical music and pretend you are far, far away?

Suddenly, I don’t want to be anywhere else but the musty-smelling studio where the old piano and its yellowed keys stare at me. When I’m inside the studio, I’m away from the world. Everything is safe, and there is nothing to worry about. Dancing – like reading and writing— is to exist in another dimension. The earliest memory of a story I wrote, roughly around three, entails being part of a circus where I run away with the lions, live in a colorful tent the color of the sea, and move every few days from place to place.

In the wake of my tenth birthday, my mother takes me on a train to Sydney, four hours away. It’s what we call the “Big Smoke” in Australia. We go to the big Bloch dance store in the delicately carved Queen Victoria building to get my first pair of pointe shoes. I rise up and up, the sales lady holding my hand. At first, it feels like she is holding my life and future. Ten-year-olds are supposed to be innocent creatures, not worried about their future. I am never not concerned with what I will become, never free from planning how I will break out of these small-town traps.

“You can go on your own now,” the sales lady says kindly.

I can become something if I can do this. My life depends upon it. I let go and begin to spin by myself. In my chaotic orbit, I lose my footing, falling to the wooden floor. But the earth doesn’t move, and I pick myself up. This is worth it. And I am never afraid to fly or fall again.

From that moment onward, my life has existed on that precipice, tiptoeing across that threshold, always ready to fly or fall.

As a small girl, whenever I’m not dancing, I’m writing. I use my body to tell stories when I cannot find the right words. I hate my body. Yet she says things I cannot. Although she’s me, she’s also someone else. She is a chameleon who transforms into a confident character, can throw her leg high in the air, and can contort the way kids in my school class cannot. Dashing, leaping, free, she’s more like light than water or air.

I want, more than anything, to be free.

Mostly, I love to make up dances and improvise steps. I’m not only attracted to Bach or Beethoven but to honkytonk songs on my father’s old radio or crescendos played at the end of movies. Just anything to be different. Disruptive.

At eleven, my new teacher, the young and delicate-boned Miss Michelle, purses her lips at my terrible turn-out. She guides me to “lick the floor,” essentially gliding the ball of my foot along the ground as I point and retract my leg with every tendu. I am the only person in class who must hold pencils when practicing the port-de-bra with his arms.

It is painful to be singled out. Yet then my feet and arms transform into something else. Something special. I am no longer an awkward child but a caricature of a real ballet dancer. As my twelfth birthday approaches, Miss Michelle hires me as an assistant teacher, and I earn five dollars an hour helping or ten dollars if I teach the whole class of budding ballerinas all by myself. Those little checks come with the scent of breaking free.

A few years later, I am off to a performing arts boarding school in Sydney called McDonald College. I hug my parents goodbye. With a spasm of sadness, I angle my face toward the sunlight so they cannot see I am crying.

It’s an incredible place of talent and maturity, of students supporting other students rather than trying to tear them down. Technically, I am nowhere close to being the best. I don’t have long legs, killer strength, or supernatural turn-out. However, I have an ability few dancers can fully develop—soul, the ability to communicate my emotions through all my limbs. I can manipulate tempo, stretching each movement like an elastic band, blending one move into the next, and experiencing the music as if it were coming from within me and not from speakers on the other side of the studio.

I choose to study dance for my final exams at the urging of my contemporary teacher, Normal Hall, who has had an enormous influence on my life as a dancer. There is a vast amount of creativity involved here, as well as choreography. Yet, like writing a story, the dances we create for ourselves should always have a motif—a distinctive movement with deeper meaning. This action can be altered, reversed, adapted into phrases, and woven delicately throughout the routine.

Just like I did when I was a little girl, I select music that goes against the grain of traditional classical ballet and contemporary norms; setting entire routines to heavy metal songs by Rammstein and Celtic Woman lullabies without instruments. When I choreograph, I am not just choreographing a three-minute performance. I am choreographing my life.

The study of dance as an academic subject also involves hours of analyzing videos of great performances and their histories. As Alvin Ailey’s “Revelations” and Judith Jameson’s “Cry” portray the writhing, sharp contortions of despair, I can paint a picture of the 1960s American Civil Rights Movement. Watching and re-watching Ballet Rampart’s “Rooster” set to the Rolling Stones, I trace every motion in “Ruby Tuesday” back to the hippie hedonism of the London streets. I am exposed to the movement rituals of indigenous tribes and the transformation of cultures by seeing what dances they kept and what dances withered with time. I am enamored with the minimalism of Fosse and the way the body transcends light in Jiri Kylián’s “Fallen Angels.”

Through dance, I understand the world. One afternoon, in sweatpants and a leotard, I promise to see and understand these far-flung places and leap across the continents.

And it is dancing that first draws me to strong, independent women.

Martha Graham grabs my spirit and does not let go. Her sharp body angles, perfect bone structure, dramatic contractions, and then release captivate me. Mostly, I fall for her irrepressible independence, a woman with snowy hair who danced well into old age draped in beautiful scarves and circular dresses, never accepted no, and carved a trailblazing path at a time when women were not supposed to do that.

At seventeen, my mind starts to break before my body does: grappling with cataclysmic-feeling career decisions nobody but I can make.

I rehearse all day and all night for the final end-of-year performance at the Sydney Opera House for weeks on end. I am eighteen, confused, depleted. In a studio stuffed with bodies, my dance partner lifts me high into the sky. I imagine it before it happens. I am floating, unafraid of falling. The walls blur around me as I spin and leap, and I cannot remember where I am. Is anybody there? My partner is not there; nobody is there. I sail toward gravity. For a split second, I recognize that I can correct my position and delicately break my fall.

But I don’t do it. I don’t know why I don’t do it. Crack. My ankle hits the floor first and cracks again. The music stops. Faces rush toward me, eyes wide open. I sob uncontrollably, not out of pain but out of relief. I need a break. I needed a decision to be made for me. I cannot admit to myself that I don’t know if I have the stamina to dance forever. I don’t know what I want.

With an ankle fractured in two places, the decision—and at least the immediate one – is determined.

After a lifetime of dancing, you become accustomed to injury. You have little choice but to embrace healing, observing the ankle take on a little more weight as weeks become months and the severed foot comes back to life. Every gram of extra body weight sustained by my foot is a victory.

My ankle never quite deflates to its standard size. After school, I enroll in university and still take on small dance jobs. Restlessness gnaws. I book a one-way ticket to New York to complete my final semester.

My dad drives me to Sydney airport on a dreary winter’s morning. Embracing him a little longer than I usually do, I feel again like a young teenager disappearing into a boarding house. However, I am a twenty-year-old with money and ambitions, even if I have no clear picture of what they are. I still love to dance and write, but no one ever told me you could make a living doing the latter.

Then I run. I run straight into the departure terminal and don’t pivot my eyes back, afraid I will change my mind. I don’t want to see my father’s face flushed with worry, love, and loss. I wish only to shed my past and be someone different, spontaneous and well-traveled, far removed from a country town coal miner’s daughter.

I depart a drizzling Sydney with only a backpack in late August 2006 and land at JFK just before a fiery thunderstorm. It is the kind of late summer storm that fragments the skies without warning and will not stop until the streets are swimming in brown flood water. Never mind, I am swept up in lust with everything about New York City: the grit of the concrete jungle, the thick black coats stuffing the streets, the electric pace, the Broadway lights, the hazy jazz bars, the tiny dance studios, the endless rows of restaurants still bursting with martini sales into the early hours.

I convince a retired banker in Dumbo (before it became cool) to let me rent his windowless loft. I walk across the Brooklyn Bridge each day to class, paying homage to the crumpled Twin Towers, still a vision of rubble. I have yet to understand those towers’ profound role in my later war journalism life. A professor offhandedly mentions “an internship in journalism,” and my interest is piqued. We don’t have internships in Australia. We just get jobs or do unpaid work experience for a week to slap on the resume, but I have heard about these from American movies.

I apply to many places, and FOX is the only one to respond. Everyone else wants to be on the broadcast. But I am far more interested in this emerging “digital thing.”

In these days before super-strict labor laws, I come into the newsroom even on my days off and learn every tool on the production line. When my byline begins to appear, I clap internally with excitement and make it a point to try and work with every section editor, learning a little more about the process along the way.

A few weeks into my studies and internship, I attend an advanced ballet class at Broadway Dance. Afterward, as I stuff my bag with my shoes and sweaty clothes, the teacher approaches me in the hallway.

“You really should be doing this professionally,” she surmises. “You have perfect feet and the perfect body for ballet. You were made to do this.”

There it is – the perfection I had fought for all my life.

But something had changed; something had softened. I was no longer sure I wanted that thing I had spent so many years seeking. I zip up my ballet bag, draw a deep breath, and meander through the friendless illumination of Times Square, knowing that I will never – I can never – walk back into that studio again. Deep down, I realize the dancer in me is not filled with enough fire, enough will, to really want it. Somewhere along the journey, the zest faded into a conditional love that could never sustain me through the cut-throat industry.

My gut tells me that there is another way, although I cannot see it. So, in the middle of a nondescript New York City afternoon, I stare up into the glittery neon night sky and with an exaggerated exhale, I let it go. I let the life I always thought I was supposed to live slip through my fingers and into the blackened gutters.

I bawl for hours inside my freezing Dumbo loft, like a lover peeled from her love, mourning the thing I had once cherished most in the world. Dance was the thing that taught me to fly, not to panic when the bottom fell out from beneath, to rise right up again. It served as the one mainstay that instilled a heavy work ethic and discipline, the loyal constant that was always beside me when there was nobody else.

I understand what my mother meant all those years ago. Dance was the medium that raised me, provided a place for my loneliness and melancholy to go and feel seen and acknowledged. I could not be lonely when I was dancing.

But as the cliché goes, one door closes only for another to swing open. I never considered a career in journalism until an offer arrived out of the blue from the head of digital, Ken LaCorte, who had an eye for determination and diligence.

Almost twenty years later, here we are. Dancing taught me everything I needed to know about myself and the world, including how to never stop rising and falling.

There is more similarity between ballet and war reporting than you realize. Both ballet dancers and war reporters live lives defined by discipline, sacrifice, and an unwavering commitment to their craft. Each enters a demanding world where the body and spirit are pushed to extremes—one through movement, the other through bearing witness.

Both tell stories: dancers through silent expression, reporters through raw truth. There is a shared yearning for authenticity, emotional catharsis, and revealing something more profound about the human condition. The stage and the battlefield may seem worlds apart, but both require courage, grace under pressure, and an intimate relationship with pain and beauty.

THANK YOU FOR YOUR SUPPORT. I LOVE GETTING FEEDBACK FROM MY SUBSCRIBERS! PLEASE EMAIL HOLLIE@HOLLIEMCKAY.COM WITH ANY SUGGESTIONS ON TOPICS YOU WOULD LIKE TO SEE COVERED.

For speaking queries please contact meta@metaspeakers.org

For ghostwriting, personalized mentoring or other writing/work-related queries please contact hollie@holliemckay.com

Follow me on Instagram and Twitter for more updates

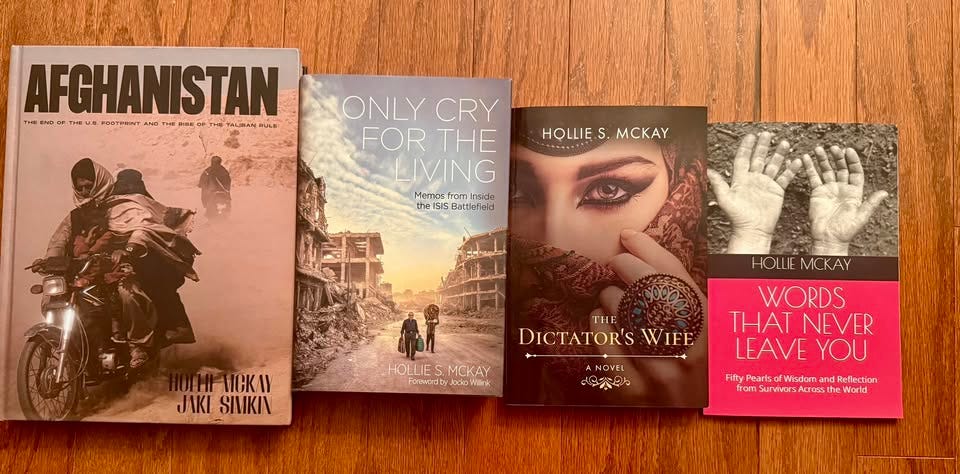

Click to Purchase All Books Here

Your writing is beautiful. I took ballet lessons and piano and was a great disappointment to my parents that neither stuck with me or I with them. I adore both as the magical performances of others. I found expression as a psychotherapist working with and writing about trauma and anxiety, and now in my later years have added a new and wonderful practice with watercolors. I just read this in your piece today and wanted to bookmark it: “When I choreograph, I am not just choreographing a three-minute performance. I am choreographing my life.”

Thank you. You gave words to my feelings.