Video: Dispatch from Afghanistan: Will the Taliban ever be recognized while it still promotes suicide bombing in its defense strategy?

“The supreme art of war is to subdue the enemy without fighting.”

― Sun Tzu, The Art of War

KABUL, Afghanistan – In Kabul, on an unremarkable Friday morning, I sip tea in a café garden. The next moment, the sound of a mammoth explosion blocks away cracks the air, followed by the crackle of gunshots, wailing police sirens, and a pillar of black smoke ascending into the warm air.

Only nobody around me seems to flinch. Nobody strains their neck to find out what and where is under attack; nobody even whispers among themselves. After all, bombs and blasts and suicide attacks are all too synonymous with this country, even amid its early and fragile post-war period.

On this occasion, a car bomb detonated as worshippers were exiting the high-profile Wazir Akbar Khan Mosque. No group has claimed responsibility for the at least seven dead and 41 wounded – although the assault bears all the hallmarks of the ISIS insurgency still reigning terror throughout the country. But unnervingly, the barrage is just one in a routine flow of targeted eruptions in recent months.

And it is for this very reason that the Taliban, officially termed the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, makes no secret of the fact it is keeping suicide bombing as a deeply revered central tactic in its national defense strategy, even though the group transformed from an insurgency into a government more than a year ago.

This begs the uncomfortable question: can the Islamic Emirate ever be formally recognized by the United States and other western countries with such a policy in place? Much is made in the media about the halt on girls’ education as a means for not accepting the group, but little is said about the ethics of suicide bombing within a formal administration.

Whereas the former insurgency relied upon the brutal technique in its offensive protocol throughout the course of the two-decade, U.S.-led war, it is now seemingly a pivotal part of its “just in case” scenario and deeply institutionalized within every one of the Taliban’s armed wings. (However, the Taliban top-brass almost uniformly denies any security concerns and doesn’t acknowledge the existence of ISIS, instead referring to such attacks as having been carried out by “criminal cells.”)

“None of these groups controls a single inch of Afghan land,” one Talib representative reminds me.

Vividly, I remember late fall, listening to another horrific ISIS terrorist attack play out at a military hospital while sitting at that same Kabul café in the Shahr-e-Naw neighborhood. Minutes later, Taliban-flown helicopters cut through the clear skies, and although no official would confirm, the rumor was that the Taliban dropped a suicide bomber on the roof to put an end to the ISIS attackers instigating the siege.

A few days after the Wazir Akbar Khan mosque attack this past September, I visit the remote, dust-swept home tucked into a small village inside the Baraki District of Logar province. A group of Taliban fighters is mourning the loss of their Taliban brother Rashid, 29, who died in that very Kabul attack I heard unfold. Rashid himself was a trained suicide bomber, and the notion of a suicide bomber killed by another is not lost on me.

“He belonged to the Zero-Ten Directorate of intelligence and was there for prayers,” one brother, Misbah, 26, says softly, his thick black beard angled toward the cement floor.

They were a family of seven brothers. Another brother, Muqadas, assures me that “Jihad is the obligation of every Muslim,” and they all remain firmly committed to doing whatever is asked of them. I learn that Rashid did one year of suicide training at what the men call “a center” in the Afghanistan hinterland, followed by “two to three years more training in Pakistan.”

“Until you are a teen, you don’t understand anything. But once you get to your teen years, you understand – and then is when we get the love of Jihad,” he explains. “Even if all the brothers die (as suicide bombers), we have no regrets.”

They proudly tell me that their village was the “first village in the whole country where Jihad started against the government” during the two-decade war.

From the Taliban’s purview, suicide bombing serves as something of a great equalizer in the war theater. Whereas the U.S. brought billions worth of aircraft, artillery and heavy weaponry to the battlefield, the Taliban leaned more and more on the suicide blueprint knowing all too well that such a stratagem would never be replicated by its enemies.

But even after effectively winning the war in the late summer of 2021, as the U.S.-backed government crumbled, the new Emirate was quick to exalt the continued practice. Just a day after the final American plane departed the Kabul skies, the Taliban flashed their Istish-haadi (“seeking martyrdom”) suicide squadron across national television, complete with the parading of suicide vests, car bombs and plastic jerry cans typically used for the creation of improvised explosive devices (IEDs).

On another morning, the Emirate’s Interior Minister Sirajuddin Haqqani honored suicide bombers at a prestigious gathering inside Kabul’s InterContinental Hotel, promising their families cash and land in gratitude for the sacrifice made by a loved one. The Haqqani Network leader stressed that “without fighters seeking martyrdom, we will not be able to finish the infidels.”

Just a few weeks after the fall last year, I visited a kindergarten on the fringes of the capital, which I quietly learned had been transformed into a suicide training center for carefully selected students under the umbrella of the “Badri Command.”

“One has to have already done special actions,” Hafiz Badry, a 29-year-old commander and native of Helmand Province, said of the selection process.

His fellow fighter, a 26-year-old unit leader assured me that the Command continues to be deluged with young fighters desperately vying for the chance to blow themselves to bits in the name of Islam and fighting for their country.

After selection, the specialized bombers undergo training that typically lasts between 40 days and two months, focused dually on preparing them physically to understand explosives and move undetected and then intense religious studies to ensure they are committed enough to pull off the life-ending mission.

As I have come to discover since then, there are an array of suicide bombing/martyrdom brigades with different names, attached to different armed units and some independent of themselves. The suicide operations may vary, but the mission is essentially the same: to neutralize anyone of thing deemed a threat and remind any foreign meddlers who is in charge.

On another twilight afternoon in late September, I meet another Taliban fighter named Ibrahim at his extended family home in Kabul. He is 28 years old, serves me tea and wants to know why I am not staying for dinner as he talks about his brother.

The brother blew himself up at a campaign rally in Parwan, north of Kabul, in September 2014, killing at least 26 civilians and wounding more than 42. The Taliban claimed responsibility for the onslaught, referring to the gathering as a “military target.”

It was a “proud moment,” Ibrahim observes without hesitation, as they had to make sacrifices to “fight the foreigners invading the country.”

For his part, Ibrahim says he spent several years “taking part in the Jihad against the foreigners that were here.” He notes that several of his brothers went to a martyrdom training “center” in Pakistan. Ibrahim does not know if and when his siblings will be called for his final mission.

Moreover, the Taliban of today vows that it is far different from its first ruling incarnation of the 1990s; that is true when it comes to the suicide bombing gambit – as it was not a thing for them back then and is still something of a relatively new phenomenon.

The U.S. National Counterterrorism Center pinpoints the first suicide attack to 1881 in Russia, when an assailant threw an IED under the armored carriage of the Tsar near the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, Russia. However, the first known suicide bombing happened at the Iraqi Embassy in 1981 in Beirut, Lebanon, when an operative for a Muslim fundamentalist group successfully targeted Iraq’s Ambassador to Lebanon.

In spite of this, the Taliban did not adopt the tactic until 2003, when the war was already well underway, and it has only grown in value ever since.

Indeed, it possesses just as much ideological importance today for the Taliban as it does strategic value. Continued training and readiness for such a tactic is also a negotiating tool, a deterrence. At any given time, thousands can be deployed to a tenuous border, as is what reportedly happened last year when tensions with Tajikistan spiked.

“They will not blow themselves up on us,” Akif Mohajer, a longtime Taliban member and spokesperson told me with a sly smile last year, referring to the group’s cadre of suicide bombers. “They are part of the Special Forces. If anyone or any country tries to move against our interests, they will be used.”

According to a 2015 analysis by the Action on Armed Violence (AOVA), “carrying out suicide attacks in certain circumstances is not illegal per se. They can, and have been, used legitimately as weapons attacking military targets.” However, if executed upon civilian population or civilian targets – as is the case with most suicide attacks across the world today – it constitutes a war crime in violation of international human rights law.

While commonly used by an assortment of paramilitary, terrorist and insurgent outfits globally, from al Qaeda to ISIS to Hezbollah and Hamas, I could not find another example of it being part of a state’s defensive game plan. Well, at least not blatantly.

But whether this becomes a cause for concern as talks between Washington and the Taliban – desperate for international recognition – resume remains to be seen. So far, it does not appear to be on the talking table.

Maiwand Naweed contributed to this report

CLICK TO READ IN PARADOX POLITICS

CLICK TO READ MORE IN THE LIBERTY DISPATCH

CLICK TO READ MORE ABOUT LIBERTY’S SUPPORT FOR VETERANS

Please follow and support my investigative/adventure/war zone work for LIBERTY DISPATCHES here: https://dispatch.libertyblockchain.com/author/holliemckay/

For speaking enquires please contact meta@metaspeakers.org

Pre-order your copy of “Afghanistan: The End of the US Footprint and the Rise of the Taliban Rule” due out this fall.

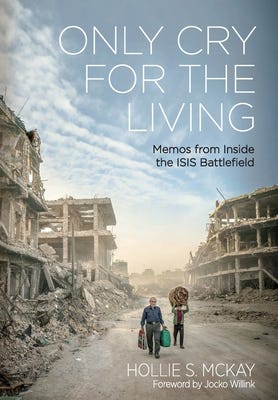

For those interested in learning more about the aftermath of war, please pick up a copy of my book “Only Cry for the Living: Memos from Inside the ISIS Battlefield.”

If you want to support small businesses: