“In the midst of chaos, there is also opportunity.”

– Sun Tzu, Chinese General/Military Strategist/Philosopher

The Swedish oil company Lundin Energy's executives have been under investigation for war crimes since 2010. Last November, Swedish prosecutors finally brought charges against the company's chairman and CEO for "complicity in war crimes committed by the Sudanese army and its allies in southern Sudan from 1999 to 2003."

Lundin Energy (then Lundin Oil) began exploring in East/Central Africa more than 20 years ago, even as a vicious civil war raged. Specifically, the prosecution alleges that company executives requested the Sudanese government seize a potential oilfield by force, making the public energy firm complicit in war crimes committed by the Sudanese army against civilians.

More than 160,000 people were forced to flee their homes due to the long-running conflict. At least 12,000 people were killed in the region between 1997 and 2003. For years, Sudan waged war in South Sudan, which became an independent state in 2011.

Cases centered on “aiding and abetting war crimes” are exceedingly few and far between. The Lundin charges, vehemently rejected by the corporation, mark the first time a company has been held to the fire for war crimes since the Nuremberg trials. In accordance with international law standards, victims of human rights violations have a legal right to remedy and reparation. A retribution order, however, can only be obtained by those present in court – which is some 3800 miles away in the case of Lundin – leaving most survivors empty-handed.

Yet, this is a landmark case, with many legal experts and international observers closely watching: what is the extent of outside influence in driving an internal conflict to secure oil?

According to a United Nations panel in 2019, the oil industry in South Sudan, which was caught up in its own war soon after gaining independence, was “one of the major drivers of the violence, suffering, and violations of international humanitarian law visible in that country.” The panel cautioned foreign companies that they were potentially complicit in war crimes and abuses.

The United States has relied heavily on free flow of petrol to bolster the world economy and maintain its global hegemony since World War II.

As the Cold War erupted around 1948, a steep new foreign policy concern for Washington appeared: the fear that the Soviet Union may dominate oil supplies in and out of the oil-rich Middle East. It gave rise to an obsession with the lingering Soviet footprint in Iran. It also raised the possibility that Iran and its neighbor Iraq may exploit the additional reserves to pose a threat to the United States and its allies.

(Baghdad mornings. (c) Hollie McKay)

Later, as a result of the 1991 Gulf War, some analysts suggested an increased U.S. footprint would boost trade with the Gulf over Asia and Europe. Furthermore, being on the ground would be an important political bargaining chip for American companies looking for contracts in the region.

Even so, the big question remains: if the U.S. had been the world's top oil producer nineteen years ago, as it is today, would the 2003 invasion of Iraq have happened?

At the time, supporters of the invasion argued that it was not a "war for oil." Instead, they pointed to Saddam Hussein's history of invading neighbors, supporting terror, and seeking weapons of mass destruction.

It is undeniable that the Iraq War was about oil, whether it was for oil or not. Iraq had previously invaded Kuwait, one of the world's leading oil producers. In the months preceding the invasion, Saddam threatened Saudi Arabia - the world's oil superpower at the time. The aggression of Iraq also threatened the Persian Gulf, the world's oil superhighway.

But Iraq itself was also at risk of being severed from the global stage. In 2003, the U.S. Department of Energy estimated that Iraq had 112 billion barrels of oil reserves. The United States, on the other hand, played a relatively minor role in international energy markets.

Whether it was the threat of radical Islamic terror, or military expansion by nation states, or simply the threat of chaos across the Middle East, America – and the allied West – had to keep the oil flowing.

Former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan wrote in his 2007 memoir, “I am saddened that it is politically inconvenient to acknowledge what everyone knows: the Iraq war is largely about oil.” That same year, Nebraska Republican and former Senator Chuck Hagel told Catholic University law students, “People say we’re not fighting for oil. Of course we are,” while Gen. John Abizaid, former head of U.S. Central Command and Military Operations in Iraq, agreed that “of course, it’s about oil; we can’t deny that.”

Fast forward to 2019.

America is now the largest oil producer in the world thanks to the fracking revolution. As of just a decade ago, U.S. production has more than doubled what it was when U.S. commitment in Iraq was at a peak with more than 135,000 military personnel. Yet it wasn't until 2018 and 2019 that America's own shale boom hit unprecedented heights, when West Texas Intermediate (WTI) traded at a cushy $53 to $72 per barrel.

“U.S. oil and natural gas production has made a significant contribution over the last decade to the U.S. and global energy security. First, it added liquidity to oil and gas markets,” observed Brenda Shaffer, a research faculty member of the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School and a senior advisor for energy at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD) in Washington DC. “The surge in U.S. production during the first part of the last decade enabled the Obama administration and the Trump administration to remove Iranian oil from the market, without causing a major rise in oil prices.”

The development of petro-power led to a change in foreign policy. Would today's America intervene in the Middle East as it did almost two decades ago? Would 100,000 American soldiers be deployed if the proxy war between Iran and Saudi Arabia in Yemen directly threatened the Saudi oil fields?

“In my opinion, 80 percent of the reason for going in [in 2003] had to do with oil and the war machine,” said Carsten Pfau, economist and founder of the Agri Terra Group. “The Iraq invasion wouldn’t have happened if America had its energy independence back then.”

Trisha Curtis, president and CEO of consulting firm PetroNerds, told me last year the Iraq war “may or may not have happened in 2003 if the U.S. oil industry was booming and production was at the levels we see today.”

“Nations typically do not go to war for one reason and one reason as simple as oil,” Curtis contends, pointing out that U.S. companies did not do well in Iraq, nor did they have a heavy or exclusive presence.

Nevertheless, the fact that U.S. foreign policy has been freed from the burden of energy dependence is hard to ignore. Consequently, the United States has more leverage against a rogue Iran, whose threat to oil supplies and the Persian Gulf has been minimized, or an aggressive Russia, whose gas-pipeline politics can be countered by LNG tankers filled with Pennsylvania products.

It is for this reason that some foreign policy analysts are raising an eyebrow over the Biden administration's energy policy: blocking the Keystone XL pipeline, issuing executive orders that limit U.S. production on federal lands, and declaring a reduction in carbon emissions of 50 percent by 2030.

“This means that there will be lopsided production around the world, and the U.S. and western nations and Asian nations will most likely be increasing their imports from the Middle East and Russia,” Curtis surmised. “The broader geopolitical issues for global oil production are the increasing likelihood that stable nations with institutions and the rule of law end up reducing oil and gas output, reducing global energy security, and increasingly relying on imports from less stable and predictable regions of the world.”

According to a 2018 study by Securing America's Future Energy, the Department of Defense spends about $81 billion annually to protect supplies around the globe. A quarter of the world's oil is produced in the Middle East, but it contains almost three-quarters of all known reserves.

It does not mean that the U.S. will go to war for oil. Nonetheless, it does mean that peace and stability in the Middle East and other parts of the world may impact U.S. and global energy security policy.

To fuel its vehicles, aircraft, ships, and ground operations, the US military uses an excess of 100 million barrels of oil, more than any establishment in the world. Thus, ease of oil access is crucial to national security and military prowess in more ways than one. Hence, the U.S. spends around $81 billion a year to defend oil supplies worldwide, according to an estimate by Securing America's Future Energy.

A 2013 policy brief featured in International Security also surmises that “between one-quarter and one-half of interstate wars since 1973 have been connected to one or more oil-related causal mechanisms.” The paper concludes that “no other commodity has had such an impact on international security.”

That’s a point tough to argue.

Although many U.S. enterprises, including the Pentagon, continue to develop energy alternatives to increase independence and free up resources for other pressing military needs, the need for oil will not go away soon.

Oil is a globally traded commodity, and the U.S. cannot be insulated from imports or exports. Similarly, Americans cannot be insulated from price fluctuations. There are also different types of crude used for other purposes, and refining qualities in different regions.

Yet, more involvement overseas could lead to more wars and war crimes.

In 2019, President Trump also caused a firestorm by declaring that he would maintain U.S. forces in Syria to control - and profit from - the oil fields. It immediately sent tongues wagging that he violated U.S. and international law, thus falling under the category of "pillaging" since oil belongs to its respective governments.

There are so many problems in this world that people should not have to deal with this one.

But what is the tipping point? At what point is war for oil a war worth fighting?

For speaking queries please contact meta@metaspeakers.org

Order your copy of “Afghanistan: The End of the US Footprint and the Rise of the Taliban Rule” out now.

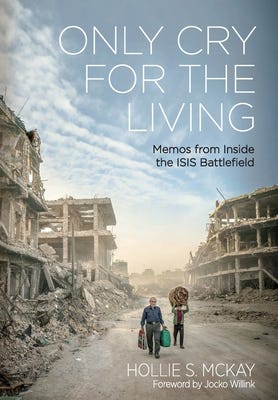

For those interested in learning more about the aftermath of war, please pick up a copy of my book “Only Cry for the Living: Memos from Inside the ISIS Battlefield.”

If you want to support small businesses:

And also now available Down Under!

Thanks again for your support. Follow me on Instagram and Twitter for more updates

Share this post