What life is really like for an Afghan women in 2023: “Where else is there to go now? The world has forgotten.”

Masooda Omari is soft-spoken, light-eyed, and thirty-four. But like many Afghan women under Taliban rule, she moves with a heaviness far beyond her years.

Two years ago, in the late summer of 2021, the insurgency returned to power as the U.S. departed and overnight plunged the country into its perception of life in the immediate aftermath of the Prophet, unraveling the rights of women in one iron-fisted swoop. Yet for Masooda, small victories of self-determination matter. And that means not completely surrendering her small sliver of independence, the vocation she loves most.

“I used to work in a sewing factory. I was the master and had fourteen tailors under me. As a master, I worked for a year, and before that, I was a trainer at a tailoring course,” she tells me wistfully from her Kabul home. “Life changed a lot with the government change.”

Masooda’s brothers – American-trained military and university professionals and family breadwinners since the death of their father fourteen years earlier – lost their jobs. Her three unmarried sisters, one a midwife and the other two lab technicians, can no longer go to local hospitals to work. The onus of responsibility has since fallen on Masooda to make ends meet through at-home tailoring, even though she can no longer freely leave her home.

However, she continues sadly, there are barely enough funds for a few loaves of bread and rice each week. Only Masooda does not complain. Like almost all Afghans now in the throes of struggle and starvation, it makes no sense to complain.

“We don’t have much tailoring work. The situation has changed for everyone, and everyone is in crisis,” she continues. “People think, rather than spending money on clothes, why not spend it on food items? Before, it was much better as we worked outside and inside the home, making clothes. I try to sell suits and children’s clothes to nearby markets, but the items from last year haven’t been sold yet.”

Although only educated until the 5th grade herself, Masooda remembers little of life before the American footprint emerged in 2001. While we can argue all day about the cons of the long-running war and occupation, she notes, the most flagrant upside was that women were no longer banished to basements to neither be seen nor heard.

“Women got a lot of freedom. We could go to university and work in offices and outside the homes,” she says stoically, as if talking about a faraway time or place. “Not everyone needed to work, but for those who needed to, this was excellent for us.”

When I ask what Masooda’s life outside the home is like, she stares through a fractured window in silence for a moment, a map of anguish stamped on her face. Like phantoms risen from the dead with kohl-rimmed eyes and Kalashnikov’s cradled in their arms, the Taliban command every street corner, patrolling every corner of the war-wracked nation in open trucks.

“We are not comfortable with some things they say. We were covering our heads with scarves even before they came, but now we put masks on and make sure to cover our faces, too,” Masooda says, her voice dropping to a reflexive whisper. “A few women still wear tight jeans or other (western) items, and the Taliban stops them and beats them.”

Yet even for the victorious Taliban, Afghanistan seems like a sallow triumph. This giant, slow-motion public health crisis spirals as deep freeze – the most severe in over a decade – blanketed much of the landlocked nation, which then morphed into a strangling heat. International aid organizations departed again this year due to the Taliban rulings that women can no longer work. According to the United States Institute of Peace (USIP), the January injunction impacted roughly 4,500 women workers, of which nearly 70 percent were their families’ main breadwinners. Moreover, Save the Children claims 28 million Afghans need urgent humanitarian aid to survive.

The economic and diplomatic detachment, with the international community failing to recognize the Taliban government as legitimate, also does little to ease the unfolding humanitarian emergency.

Only somehow, the daily grind continues.

“We are just surviving. Whatever the brothers make at small jobs, they give us a portion and tell me to do what I can with it,” Masooda explains. “I take care of the family with that and get food and medicine.”

But the biggest challenge is not navigating the draconian world outside, but keeping their sick mother alive at a time when basic healthcare is growing scarcer by the day.

“She is not doing good. Due to weather, her leg is swelling, she cannot walk, and her eyesight has decreased. Doctors say she should do physiotherapy every day, but it is 250 AFS per day (3 USD), and we cannot afford it,” Masooda notes, her shoulders slumped in defeat.

A series of earthquakes in Kabul several years ago snapped the frame on their fragile home, and her mother slipped into a psychotic panic about her children dying beneath crumpled walls in the dead of night. Even after her brothers repaired the damage and renovated with the money, they raised selling family jewelry and household appliances. And then, when Masooda’s brothers went off to fight for their country, their mother’s stress and sleeplessness reached epic proportions, taking a toll they felt helpless to fix.

“Our mother started stressing herself over debts and over my eldest brother, worried when he was going and coming back from his job. So many of his colleagues were martyred in the streets we live in – either by sticky car bombs or other methods,” Masooda remembers. “Our mother would be sitting on the window watching from the top until a brother who took the older brother in the car returned home. Then, at night, when it would get late, she would call him, begging him not to come home as it was dark now repeatedly.”

To be an Afghan, however, which way one slices it, is to be a victim of perpetual conflict and brutality. Masooda recalls an attack outside their home that killed a much-loved relative and how her mother wept when they returned from the funeral.

“She cried and cried, and she never stopped crying,” she says. “Then one day, she woke up at 3 am and went to the bathroom to wash her face, and when I checked on her, she had fallen to the ground.”

The stroke – which Masooda refers to as a “nervous attack” – was “due to her severe bleeding of the liver induced by anxiety which increased her blood pressure and put pressure on her nerves. Therefore, it was a nervous attack. Her mother can no longer feel her left side and is deteriorating daily.”

And although the Taliban promised to usher in a new era of peace, almost daily bomb blasts continue to wrack Afghanistan. Nevertheless, these onslaughts rarely make international news as much of the world abandoned eyes on the war-plagued nation long ago. Like almost all Afghans, Masooda takes for granted that she will survive.

“Blasts and fights still happen, people still run for their lives, and this is still the concern for everyone,” she notes. “But now we have decreased visiting family and friends not because of security, but because everyone is poor.”

However, the seamstress reluctantly admits that the Taliban’s hardline edicts are starting to rub off in society – even on her brothers, who are staunchly against the Taliban and previously took up arms against the then-insurgency.

“Regarding hijab and women working outside, yes, they share Taliban ideology,” Masooda conjectures.

Still, there are small slivers of silver linings. Nearly every week somewhere across Afghanistan, young women take to the streets in vehement protests, chanting for their right to work and learn, undeterred by the Taliban’s heavy hand and a hail of bullets punctured into the skies as an act of dispersal and intimidation. But, unfortunately, Masooda believes it is already a lost cause.

“Nobody cares about it now. Islam has given women rights, but no rights are being given. Universities are closed; the ones who studied, they did, and the ones who are left halfway or in the beginning are left right there,” she acknowledges. “We find our own ways to express ourselves. But in Afghanistan, nobody will listen. My heart wants to speak out, even if the Taliban listens, but nobody hears it.”

Masooda is, in a sense, a guardian of memory – of life before and after the U.S. imprint. And while most of her friends fled long ago, she pledges to remain in the Mothership that so many still want to leave. Those opportunities have mostly dried up.

“Our mother has fully removed the thought of going outside the country from our minds. If our mother had wanted or wanted now, it would be better; conditions and life might be better,” she adds with a cumbersome pause. “And so, I stay. Where else is there to go now? The world has forgotten.”

Maiwand Naweed photographed and contributed to this report

PLEASE CONSIDER A PAID SUBSCRIPTION TO THIS SUBSTACK TO HELP KEEP INDEPENDENT WRITING AND JOURNALISM ALIVE. THANK YOU SO MUCH FOR YOUR SUPPORT.

For speaking queries please contact meta@metaspeakers.org

HOLLIE’S BOOKS (please leave a review)

Now available on Kindle and Paperback

** Short read of meaningful lessons gleaned from the ordinary forced to become extraordinary

Order your copy of “Afghanistan: The End of the US Footprint and the Rise of the Taliban Rule” out now.

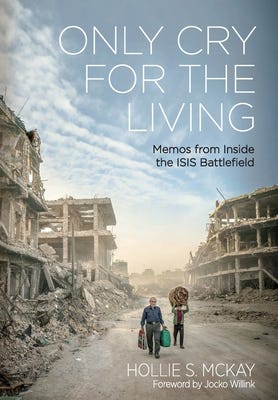

For those interested in learning more about the aftermath of war, please pick up a copy of my book “Only Cry for the Living: Memos from Inside the ISIS Battlefield.”

If you want to support small businesses: